Hideko Tamura, 91, shares about travel to Japan for 80th anniversary of Hiroshima-Nagasaki bombings, continued pursuit of peace

By Holly Dillemuth, Ashland.news

MEDFORD – Following her visit to Japan earlier this month for the 80th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings, Hiroshima survivor Dr. Hideko Tamura, also known as Hideko Tamura Snider, shared her experiences of the memorial and of the bombing with those at a Southern Oregon Japanese Association gathering at the Medford Public Library’s Community Room Sunday, Aug. 17.

It was the first trip to Japan for the “One Sunny Day: A Child’s Memories of Hiroshima” author since the 70th anniversary of the bombings in 2015, according to Estelle Voeller, chair of “One Sunny Day Initiatives,” a nonprofit started by Tamura in 2007 that promotes peace, hope and reconciliation, in pursuit of a “world free of nuclear weapons.”

One Sunny Day

Poem by Dr. Hideko Tamura

One Sunny day,

I lost my universe.

The mid-summer sun glaring in the bright blue sky,

Tall green branches quivering in the wind,

Whispering to a happy child,

Just home from a lonely country village tucked far away,

“Good morning, child, welcome home”

The Oxygen called happiness filled the air.

Shimmering lizards on the granite, moving about peacefully,

Dancing color maps in the butterfly wings,

And my kitty, Kuro-Chan catching sun rays, grooming her coat.

All were so well that day.

To be hugged and fed we stole away from the country,

For this moment of love and safety.

Suddenly from the sky, swift movement of blinding flash,

Turning into a boulder of raging heat unleashed on humans and buildings

As the scorched earth shook with deafening sound in the primordial dark.

Searing heat raging and spreading

No time to pull you out Mama, no time for you cousins.

Rivers were flowing, voices muffled, no cooling for the burns.

I watched the red sky into the night, the last of my childhood.

Hiroshima turned into ashes

My world was no more

Along with my oxygen, called happiness.

Forever changed city, Hiroshima, watched us return, scars hidden in shame

For they stirred the unthinkable, for they peeled off our dignity.

On the flowing riverbanks grew four, five, six leaf clovers.

Picked by a lone child at sunset.

Searching for her lost garden and universe, visible only in her minds’ eye.

On one sunny day, began a search for Life and that conditions that must be

On being a Human, anywhere, anytime.

“I’m so proud and happy that I was able to do that at this age,” said Tamura, 91, of returning to Japan for the anniversary. “I didn’t see the Japan I remembered, except in Kyoto … In 80 years, they’ve reconstructed.”

After decades of sharing her story of courageous survival and passionate pursuit of peace, Tamura also announced on Sunday she will no longer speak publicly about the events of Hiroshima, saying it makes her physically ill. She has conducted an estimated 250 talks and media interviews since 1979, according to Voeller, including an interview with the late Pulitzer-winning historian Studs Terkel of Chicago.

Rather than recounting the bombing in detail, which Tamura said, “always makes me sick,” Tamura read from a poem she wrote to describe it.

The morning of Aug. 6, 1945, before 8:15 a.m. was the happiest time in 10-year-old Hideko’s life, she told those gathered Sunday afternoon.

Hideko was finally home with her family after being away for some time.

Everything about the scene was welcoming, Tamura remembers.

Mild summer sun.

Bright blue sky.

Green branches “quivering” in the wind and her cat Kuro-Chan catching sunrays and grooming her coat.

“The oxygen called happiness filled the air,” Tamura said, reading from a poem.

“All were so well on that day,” she added. “I was at the top of my happiness.”

Then, at 7:30 a.m., sirens blared.

Turning on the radio, young Hideko heard, “Everything is clear – go back outside to what you were doing.”

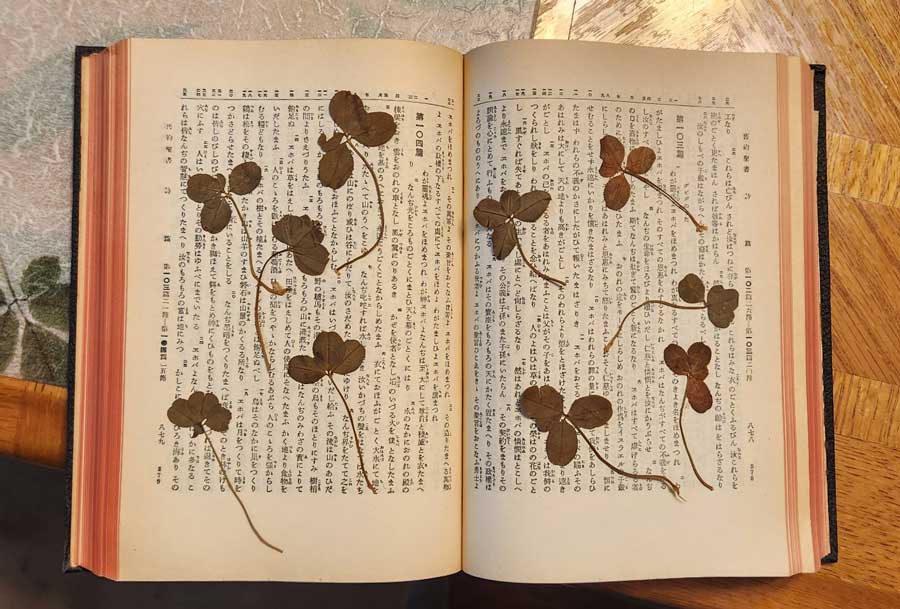

Tamura then read from a Japanese samurai book her cousin Hideyuki had given her.

“We were always exchanging and playing together,” she said.

But her life was about to change that day forever, “the day the sun and the Earth melted together.”

“Scorched earth shook with deafening sound in the primordial dark,” Tamura said, reading from a poem she wrote about the bombing. “I’ve never been in such a darkness.”

She watched as the last of her childhood was destroyed.

“Hiroshima turned into ashes,” Tamura said. “My world was no more, along with my oxygen called happiness.”

Her beloved mother was killed in the bombing.

After the attack on Hiroshima, Hideko learned she had pieces of glass in her right foot, though she was not exposed to as many harsh chemicals as others, many of whom experienced severe breathing problems and worse.

After finding out about her foot, she sought help from her aunts.

“Do you know what they said? … ‘Help yourself,’” Tamura recounted. “We’ve got to take care of ourselves, too.”

Young Hideko had always gone to her mother with even the slightest bruise, and she would fix it.

“I thought that was the way life was,” Tamura said.

That day, she realized, “Only your mother really, really cares.”

Tamura also realized that day, her childhood had ended at age 10.

“Now I have to take care of myself,” Tamura said, recalling the feeling.

“I’ve been taking care of myself ever since,” she added.

Tamura noted that, without her mother around, no one came to her graduation.

And when she won awards, “nobody cared,” she said.

Not even a hand on her shoulder or a “well done” when such affirmation was well deserved.

“My mother would have been ecstatic,” Tamura said.

Following the bombing, she recalled sitting on the riverbank by herself. She found glimmers of hope in four, five, six, seven, eight, and even nine-leaf clovers.

“God gave me happiness,” she thought.

What she didn’t know at the time was that the bomb changed the foundation of Hiroshima and its people.

“The nature of the bomb that dropped changed chromosomes in everybody and everything,” Tamura said. “It changed the chromosomes even in clover.”

She saved some of the clovers in a copy of the Old Testament she was given at her graduation.

“I still have some of them,” Tamura said.

The discovery of the clovers were a pivotal point in her life, representing a search “for her lost garden in the universe, visible only in her mind’s eye. One sunny day began a search for life and the conditions that must be on being a human anywhere, anytime, and that has been my life.”

Hibakusha means survivor in Japanese.

Kazumi Matsui, mayor of Hiroshima, shared a peace declaration at this year’s 80th anniversary of the A-bombing, referencing the importance of the “ardent pleas for peace” and the stories of hibakusha; many of whom are now in their late 80s and 90s, according to Shiro Suzuki, mayor of Nagasaki, who also wrote a declaration of peace for the memorial.

“Building a peaceful world without nuclear weapons will demand our never-give-up spirit,” Matsui said, referencing the words of another survivor.

Documentary coming

Dr. Hideko Tamura, also known as Hideko Tamura Snider, is featured in the documentary film “Seeds of Peace” which has been submitted to Ashland Independent Film Festival for the 2026 season, pending approval by AIFF, according to Estelle Voeller, chair of One Sunny Day Initiatives. The film shares the story of how Tamura brought Hiroshima Peace Trees to more than 50 cities across Oregon, including in Talent and Ashland. The lineup for the 2026 AIFF season will be released in mid-February. To learn more about the film, go to outdoorhistoryconsulting.com/seedsofpeace.

Tamura carries this never-give-up spirit within her as well.

“Somehow in my character, I don’t have a vocabulary of giving up,” Tamura said. “I never, ever gave up if I decided this is what I wanted to do.”

After all, she survived an atomic bomb.

“A life that survived — it has to want to do things to help try to bring a better world,” Tamura said.

Tamura went on to earn degrees in social work (Wooster College) and theology (McCormick Theological Seminary). She was a therapist for 40 years, according to The College of Wooster, until her retirement in 2003.

She also holds an Honorary Doctorate in Human Letters from The College of Wooster (2010), has served as Peace Ambassador for the City of Hiroshima (2013) and is a recipient of the Peacekeeper Award from Peace House (2018).

Hideko Tamura appeared in the NBC News documentary, “To End All War: Oppenheimer & the Atom Bomb” in 2023. She has also been interviewed by Chris Wallace on Fox News and by Amy Goodman for Democracy Now; served as a keynote speaker for Children’s Conference in Hiroshima and, for many years, has served as an advocate for peace, sharing with students at South Medford and Ashland high schools and Southern Oregon University. Tamura has also participated in the annual Hiroshima and Nagasaki vigil held each year in Ashland in early August to commemorate the anniversary of the bombings.

Since 2017, Tamura has worked to bring the seeds of Hiroshima’s Green Legacy Peace Trees, which she helped germinate, to more than 50 cities across Oregon, including at Ashland’s Japanese Garden in Lithia Park, Thalden Pavilion at Southern Oregon University, and Chuck Roberts Park in Talent.

“Believe me, it wasn’t easy,” Tamura said. “I have to go and go and go and go.

“But remember, I don’t give up,” she added lightheartedly. “So tell me if there is something you are hoping to do that looks challenging. I’ll be on your side, if it were helping to bring a better world where we will not have to use nuclear weapons ever again.”

Following her message, Henley High School sophomore Zoey Hyde approached Tamura with a bow and the gift of a crane made from a gum wrapper. The 15-year-old has been making the cranes since second grade.

Hyde said her takeaway from Tamura’s message was to be kind to everyone.

“I thought (the crane) might be a good way to show appreciation for her coming out and doing this, especially since it’s such a hard topic,” Hyde said.

More information

To learn more about the Southern Oregon Japanese Association and upcoming events, go to soja.ngo

To learn more about Tamura’s Sunny Day initiative, go to osdinitiatives.com/GLH

Hyde spent four years living in Sagamihara, Japan, about an hour outside of Tokyo, when her dad was based at Camp Zama. He is now based at the 173rd Fighter Wing at Kingsley Field in Klamath Falls.

She spoke fluent Japanese to Tamura, thanking her for the opportunity to hear her speak, an experience Hyde called, “once in a lifetime.” Hyde told Ashland.news there isn’t a Japanese program at her school, but she hopes to use her Japanese language skills to teach in Japan at some point.

SOJA holds events throughout the year to foster Japanese culture in the region and organizers said they have been planning her last speaking engagement with the public for about a year.

“Something that moves me tremendously is the attitude that came from (the bombings in Japan),” said Lukas Wright, president of Southern Oregon Japanese Association. “Rather than taking on a spirit of bitterness and anger, many Japanese people, including Hideko-san, took on a spirit of peace and took the opportunity to advocate for peace and the world.

“I have a son who just turned 10,” he said, his voice breaking slightly and noting Tamura was the same age when the bombs fell.

“I never understood the gravity of the bombs falling in Hiroshima until I had a child.”

Reach Ashland.news reporter Holly Dillemuth at [email protected].

Aug. 21: Corrected spelling of Kara Baylog’s name and name of college where Hideko Tamura studied social work.

![United States’ cities average electricity price per kWh. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, APU000072610], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/APU000072610, Nov. 10, 2025.](https://ashland.news/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Power-graphic-300x141.jpg)

![United States’ cities average electricity price per kWh. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, APU000072610], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/APU000072610, Nov. 10, 2025.](https://ashland.news/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Power-graphic.jpg)