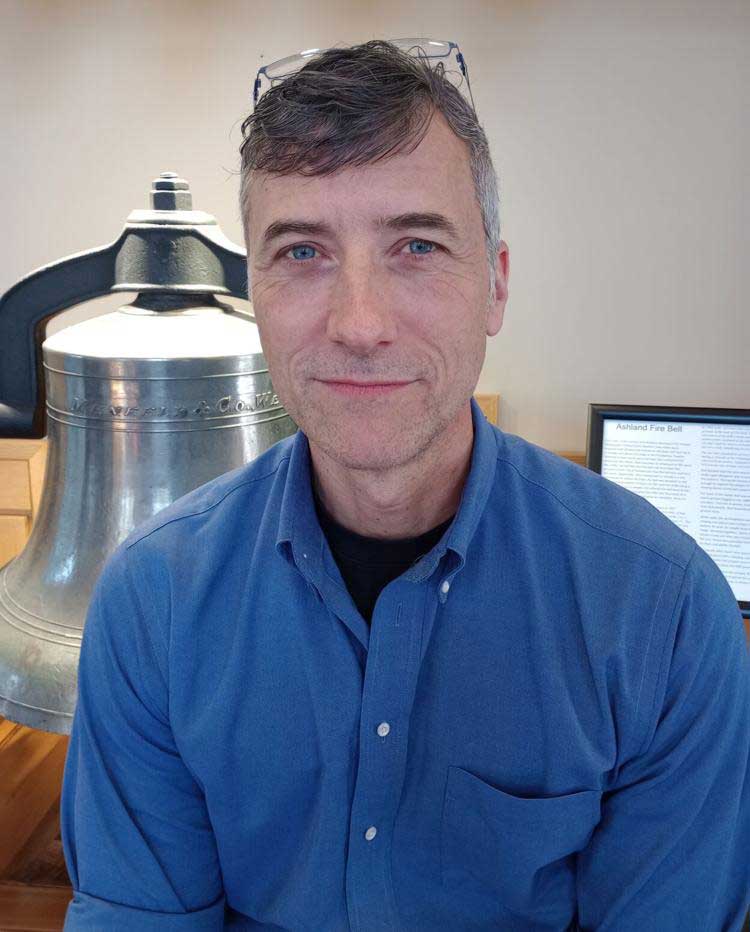

Kelly Burns, Ashland’s emergency management coordinator, shares his experience of the Almeda Fire as the then-battalion chief of a crew of eight firefighters for Ashland Fire & Rescue

By Kelly Burns

I remember the moment, 30 minutes into the Almeda Fire: I had established a forward command post in an area near South Valley View and Highway 99.

Based on what I knew, if we could draw a line and stop the fire along South Valley View, we would have a chance. Then, through my radio, I heard my dispatcher telling me there were reports of structures on fire in Talent. The fire had already jumped 3 miles past us.

I immediately ordered my Medford Battalion Chief and three other available fire engines to get to that Talent neighborhood as fast as they could to protect lives and structures. The winds would drive spot fires further and faster than we could respond. We were outmatched.

Starting in northwest Ashland and whipped by wind gusts of more than 40 mph, the Almeda Fire consumed anything in its path with terrifying speed, devastating our neighboring cities of Talent and Phoenix. It left behind a changed landscape—not just physically, but emotionally, culturally, and operationally.

Meanwhile, our residents experienced traffic congestion, confusion about evacuation routes and orders, a failure of informational systems, failure of infrastructure (electric, water, communications), spot fires igniting far ahead of the main fire, overwhelm, and panic.

Many people received no advance notice. Many lost everything. To this day, I think all of us who survived the Almeda Fire carry a fearful anticipation of the next big fire event. At the responder level, we saw some of our best efforts fail, including water supplies to our fire hydrants. One no sooner had extinguished a spot-fire on a neighborhood home when three others around it burst into flames.

What we experienced during those 36 hours and the weeks that followed continues to influence the direction of emergency response, management, and preparedness in our valley. Here’s how:

• Communication systems must be accessible

We learned that relying on a single notification platform is dangerous.

Today, Ashland uses a layered approach: Jackson County’s “Jackson Alerts” system, Ashland’s city web pages for press releases, social media accounts, the emergency radio station 1700 AM, and wildfire hotline 541-552-2490.

We also emphasize low-tech communication, including door-to-door notifications by law enforcement and emergency services. Ashland also established a full-time dedicated emergency manager position to handle the coordination and communications needed at all levels of our city and our region—that’s me.

• Evacuation planning must be specific and practiced

Since 2020, Ashland has overhauled its evacuation planning. In 2021, we mapped clear evacuation zones. These are updated regularly and accessible online. In 2024, in cooperation with Jackson County, evacuation zones were built throughout the county.

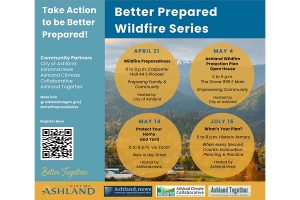

Finally, we launched multiple community education campaigns encouraging residents to know their zone, plan multiple routes, and get better connected with their community, because when the next big event happens, we all need each other.

• Community preparedness begins at home — don’t wait for 911

In 2020, many residents were frozen in uncertainty. Now, through education and outreach events, we continue to push the message: prepare before the fire, not during it. Preparedness needs to begin at a household and individual level, then expand out to friends and neighbors to work together and ask for and offer support.

Community members need to understand they have the responsibility to solve their evacuation and preparation issues. This includes defensible space around homes, home hardening, go-kits, and contingency planning for when the original plan isn’t working for the current situation.

The reality is that, in a major event, our limited number of emergency responders won’t be able to respond to every 911 call. It is each person’s responsibility to make their own plan, practice it, and connect with family, friends, and neighbors. Not all, but many, issues we will face in a fast-moving wildfire can be solved with planning, practice, and connecting with your community in advance.

• Interagency coordination is essential

No single agency can manage these disasters alone. Since the fire, Ashland has deepened its collaboration with Jackson County Emergency Management, regional response agencies, non-profits, and local businesses. In an effort unique to Oregon, Ashland, the city, Southern Oregon University and the Ashland School District signed an intergovernmental agreement creating a Joint-Emergency Operations Center to increase coordination and communications during large events.

We train and exercise together regularly with personnel from SOU, ASD, and the City to be better prepared for the next disaster.

Final thoughts

Emergency preparedness is not just about go-bags or alerts — it’s about mindset, practice, and community. What we learned from the Almeda Fire is that we need each other. No one gets through this alone. Ashland is better prepared today because we faced one of our worst times together.

We’re not done learning or preparing, but every step towards preparing together, at any level, makes us more resilient.

If there are assignments I can leave you with, it’s these: know your zone, make sure you’re signed up for alerts, build and refine your go-kits, and connect with your family/friends/neighbors on your evacuation plans. The more we prepare as a community, the better chances we all have.

Email Kelly Burns, Ashland’s emergency management coordinator at [email protected]

This column first appeared on the Ashland Climate Collaborative website.