New research sheds light on why the Franklin bumble bee may have disappeared

By John Yunker for Ashland.news

The Klamath-Siskiyou region is home to many endemic species — plants, animals and insects that can be found nowhere else on the planet — such as the Mount Ashland lupine, Siskiyou Mountains salamander and the Pacific fisher.

But this region is also home to what could be a recent extinction, that of the Franklin bumble bee (Bombus franklini), the rarest bumble bee species in the U.S.

The last confirmed sighting of a Franklin bumble bee was in 2006. And while the bee may still be alive and well somewhere in the region, what scientists want to know is why these bees became so rare. Theories range from human-influenced pathogens to pesticides to climate change.

New research published in October in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences sheds light on why this bee species declined precipitously. The answer stretches back 100,000 years.

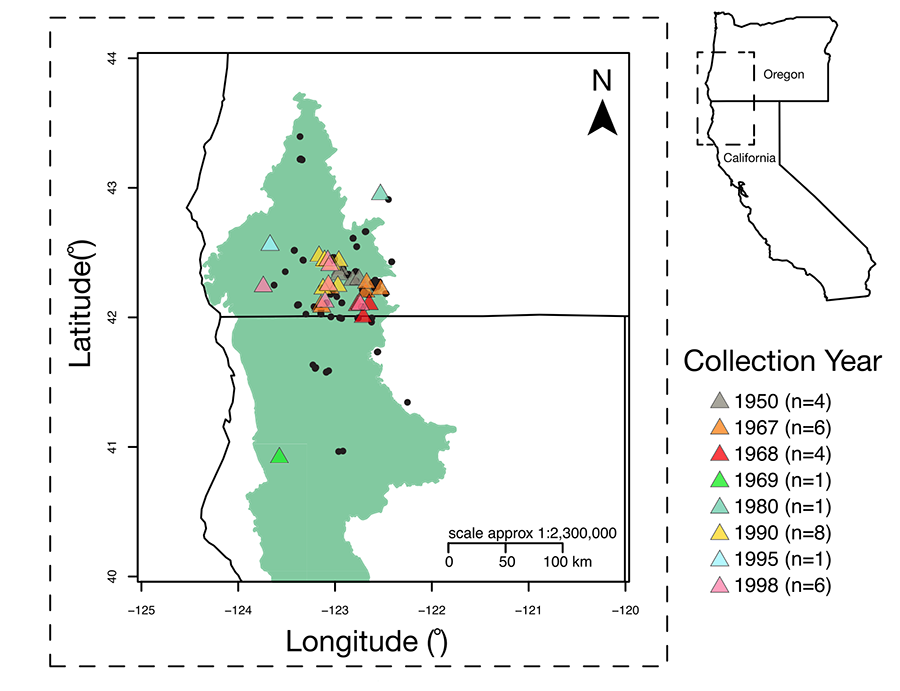

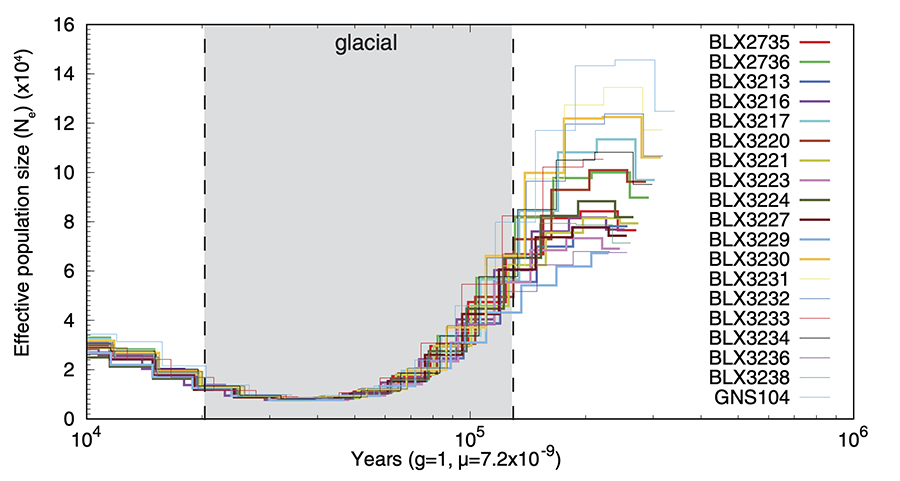

A team of nine scientists led by Rena Schweizer, a wildlife conservation geneticist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, conducted genetic analysis of 25 Franklin bee specimens collected over a period of four decades. The research found that “contrary to previous hypotheses, pathogens likely did not drive initial declines; rather, its extinction vulnerability may have arisen from population bottlenecks and environmental stochasticity over the last 100,000 years.”

“Low genetic diversity is a big part of the story of the Franklin bumble bee,” said Jonathan Koch, associate professor at the College of Natural Sciences at the University of Hawaiʻi and one of the report’s co-authors.

He noted that the species has always had one of the narrowest geographic distributions among bumble bees worldwide and this may have played a key role in its struggles. Koch contrasts the Franklin bumble bee with the Bombus vosnesenskii bumble bee, another bee species native to the region that has grown in number over the years. “The vosnesensky bumble bee, which has a range that stretches the entire West Coast of the U.S, has fared remarkably well and is quite common on Mount Ashland and elsewhere.”

The research also noted that the recent stresses from climate change may have “heightened” the species’ downturn. “Franklin intersected with humanity in a very vulnerable state,” said Koch.

Robbin Thorp’s legacy lives on

To research the history of the Franklin bumble bee, one could not easily find specimens in the wild. So the team relied largely on bee specimens from the Bohart Museum of Entomology at the University of California, Davis. Most of these specimens were collected by Robbin Thorp, professor emeritus at UC Davis, who had studied the Franklin bumble bee for decades. Many Ashlanders got to know Thorp through his annual trips to Ashland and public advocacy work. Thorp passed away in 2019.

Koch spent time with Thorp walking the slopes of Mount Ashland in search of the bee. “Sadly, I did not see Franklin,” he said. “I was a few years too late.” Koch credits Thorp for making the genomic research possible. “It was because of (Robbin’s) collections in the museum that we were able to conduct this research.”

The deets

To learn more about the Franklin bumble bee and help with the search:

To visit the Pacific Northwest Bumble Bee Atlas, click here

To visit the California Bumble Bee Atlas, click here

To download the iNaturalist app, click here

You can also check out “Bumble bees of North America: An Identification Guide” at the Ashland Public Library

Exhibit 1 shows the locations of the bees studied and approximately when they were collected. By conducting genetic analysis of the specimens, scientists could peer back through millennia relying on established mathematical models to estimate the population size along the way.

Exhibit 2 diagrams the population of the species based on 19 specimens looking back past the last interglacial period in which the populated suffered greatly “and never fully bounced back to previous levels,” said Koch. “Extinction is a long story. It did not happen overnight.”

Periods of drought and wildfire may also have taken a toll. “Historical studies showed evidence of extensive fires and drought periods, which could impact bumble bees in complex ways. While fire can benefit bees by clearing forests and encouraging understory growth, persistent drought and wildfire could negatively affect plant availability.”

The search for Franklin continues

Despite no known sighting in nearly 20 years, the Franklin bumble bee has not been declared extinct, and many scientists and volunteers are not giving up the fight.

The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation continues to search for the Franklin bumble bee. Rich Hatfield, Senior Endangered Species Conservation Biologist at Xerces, points to two collaborative research projects: the Pacific Northwest Bumble Bee Atlas and the California Bumble Bee Atlas with the Franklin bumble bee a major focus of both. “We’ve been highlighting that species and encouraging volunteers to spread out throughout the Siskiyou region and look for the bee. We’ve conducted hundreds of surveys since 2018.”

Jeff Everett with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is also leading efforts to find the Franklin bumble bee. “Jeff has been working with scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey to do some eDNA (environmental DNA) work,” said Hatfield. “This past field season scientists and volunteers collected flowers and then sent them to the lab to be analyzed to see if it’s possible that the Franklin bumble bee visited those flowers. This is another method being used to try to find the species.”

Ashlanders can ‘bee’ detectives

Bees can be challenging to identify even under the best of circumstances, as they are small, constantly on the move and often mix with other bee species. “Consider how difficult it can be to find a wolverine, let alone something as small as a bee,” Koch said. “Bumble bees live cryptic lifestyles, spending most of their time underground, making them difficult to find.”

Scientists rely on the assistance of citizen scientists armed with smartphones and apps such as iNaturalist. “One out of three bees documented on iNaturalist are bumble bees,” Koch said. He encourages more people to go outside and photograph bees.

As scientists and citizens continue their search for Franklin, the genetic research into Franklin will help other species in the future. By knowing the history of a species scientists can make more informed decisions around management, breeding programs and prioritization.

“Even though the story of Franklin is sad,” Koch said, “this research will help us better understand the Western bumble bee and rusty-patched bumble bee — two cousin species to Franklin that are currently endangered.”

Meanwhile, the search continues in the hope the answer is out there.

John Yunker is the author of the novels “The Tourist Trail” and “Where Oceans Hide Their Dead.” He is a co-founder of Ashland Creek Press and the editor of Writing for Animals (also now a writing program).