It was his money that perverted justice then and burnished his image thereafter

By Herbert Rothschild

Most of my readers, I’m guessing, are relishing the revelations from the Jeffrey Epstein files because they may do irreparable damage to President Donald Trump’s political standing. I share the hope that they will, because Trump is trying to do irreparable damage to so many aspects of political life that I value. Still, I take no pleasure in the subject.

Abstracted from its political context, the Epstein affair becomes another instance of sex trafficking, and the focus of our thinking about sex trafficking should be its victims. How many there are can only be approximated, but they are legion.

The U.N.’s International Labor Organization estimated that, in 2021, on any given day 27.6 million people worldwide were held in forced labor, of whom 3.3 million were children. Of the total, 23% were trafficked into commercial sex work. In the U.S., over 1 million are in coerced labor, but I wasn’t able to get the percentage of those in sex work.

Human trafficking has been a focus of U.S. law enforcement. At the federal level the Departments of Homeland Security, Justice, Labor, State and even Transportation devote resources to the problem. Every state now has laws against trafficking, and many, including Oregon, have special enforcement units. Jackson County has the Southern Oregon Child Exploitation Team.

Given that level of commitment to stop trafficking, especially child trafficking, the most disheartening aspect of the Epstein affair is how justice was perverted after Epstein was arrested in Florida in 2005 following a complaint by the parents of a 14-year-old girl in Palm Beach.

Miami Herald reporter Julie Brown told that story in detail in a three-part series published in November 2018 and later in a book. In 2019, after Epstein was arrested in New York and charged with sex trafficking, prosecutors declared the Florida deal shielding him from federal prosecution legally invalid.

What happened? Following the parents’ complaint in 2005, Palm Beach police launched a formal investigation. Over the course of a year they identified at least five minors who had worked at Epstein’s house and were victimized. They found ledgers, phone messages and items in his home consistent with a systematic sexual exploitation of minors. They recommended that Epstein be charged with multiple felony counts.

Palm Beach County State Attorney Barry Krischer refused. Without presenting all the victims as witnesses to a grand jury, he secured an indictment on a single count of soliciting prostitution. Outraged, the police chief and lead detective then referred the case to a nearby FBI office, saying the state charge didn’t reflect “the totality of Epstein’s conduct.” In 2006 and 2007, the FBI made findings similar to what the Palm Beach police had uncovered, including more than 30 potential victims and also that some of them were from out of state, which violates federal law.

At that time, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Florida was Alexander Acosta, who in 2017 became Trump’s secretary of Labor. Acosta negotiated a plea deal with Epstein’s legal team, which included Alan Dershowitz and Kenneth Starr. The plea involved no trafficking charges. Epstein pleaded guilty to two state charges — soliciting a minor for prostitution and solicitation of prostitution.

The penalties: Epstein would register as a sex offender, pay restitution to certain victims and serve 13 months in county jail, not state prison. There he was treated with unprecedented leniency. He was allowed to leave jail up to 12 hours a day, six days a week, to go to his office. He had a private wing with his own security. And he could receive visitors, including young women.

Notoriously, the non-prosecution agreement granted immunity from federal prosecution not just to Epstein but also to unnamed “potential co-conspirators.” And although it required that Epstein’s victims be notified of the deal, they weren’t. Instead, they were sent letters saying the investigation was ongoing, a violation of federal law.

Epstein’s status as a sex offender was never lifted. In New York State, he was a level 3 offender, meaning a high risk of repeat offense. That status required him to provide an online, publicly searchable database with his photo, his addresses, vehicle license plates and other personal information

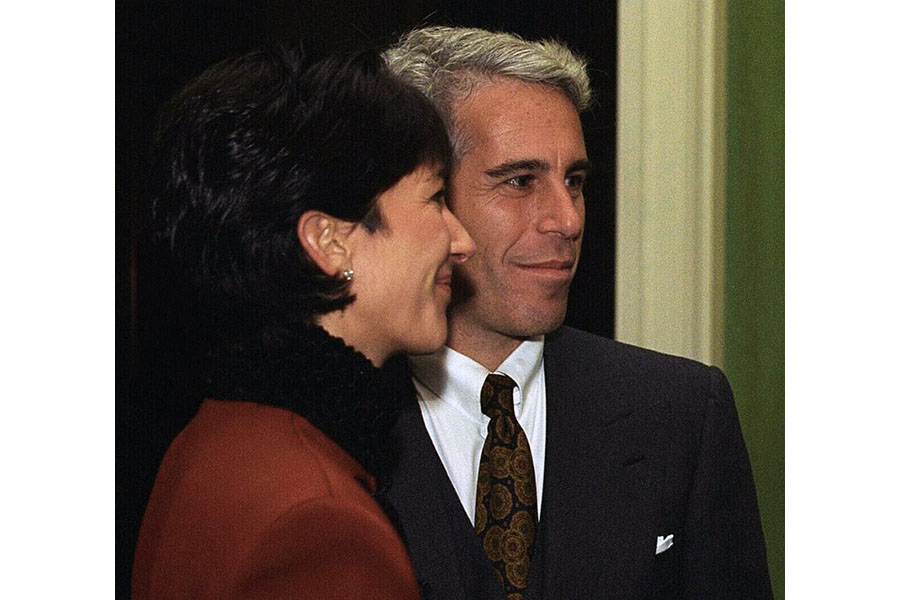

So, anyone who associated with Epstein after 2008 had no excuse for not knowing what kind of person he was. Many former buddies, like Bill Clinton, did back off, although the Clinton family continued to socialize with Ghislaine Maxwell, his main partner in the trafficking ring. Some high-profile men, however, such as Larry Summers and Peter Theil, continued their associations.

Unarguably, the worst aspect of the Epstein story is that numerous men, including men with public reputations to protect, were willing to sexually abuse minors or, knowing what Epstein was doing, were unwilling to spurn him, much less turn him in to the law. But a sad second aspect is what it says about the attraction of money. Both before and after his conviction, Epstein’s wealth allowed him to successfully cultivate connections with men of status, which he did assiduously.

Epstein donated a total of $9.1 million to Harvard University between 1998 and 2008, but to its credit Harvard refused to accept further donations from him after his conviction in 2008. By contrast, MIT received 10 donations from him totaling $850,000 between 2002 and 2017, all but $100,000 of them after 2008.

After Epstein was arrested in 2019, MIT commissioned an outside investigation into its relations with him. The report was released in 2020 and posted online. You can access it here.

The portion I found most instructive was the account of the dealings that MIT Media Lab director Joi Ito had with Epstein. Learning of Epstein’s large gifts to Harvard, Ito decided to cultivate him as a donor, despite reservations expressed by other lab staff and what Ito himself had read about the Florida case on Epstein’s Wikipedia page.

Ito was nervous, though. He emailed Linda Stone, a former member of the Media Lab’s Advisory Council, who had introduced Ito to Epstein at a TED conference. “As my adviser about these things, what do you think the risks are? I think MIT may get antsy about his background, not sure. . . . I personally feel like I want to just get to know him and if I trust him and like him, I’ll hang out with him.”

I guess it’s hard to spot a slimeball if he’s wearing a tuxedo.

Herbert Rothschild’s columns appear Fridays. Opinions expressed in them represent the author’s views. Email Rothschild at [email protected]. Email letters to the editor and Viewpoint submissions to [email protected].