Attorney, activist and Ashland High School alum chronicles her family’s efforts behind the largest river restoration project in history

By Sydney Seymour, Ashland.news

The Ashland-based Yurok tribal attorney central to the world’s largest river restoration project is set to talk about her memoir from 3:30 to 5 p.m. Saturday, Jan. 10, at the Ashland Public Library.

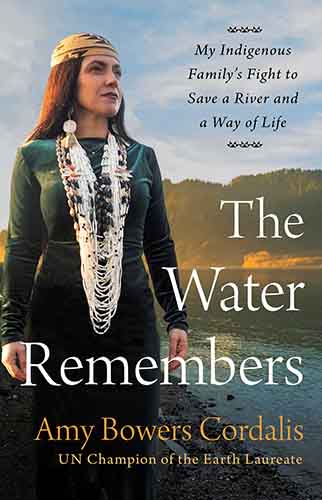

In her book, “The Water Remembers: My Indigenous Family’s Fight to Save a River and a Way of Life,” author Amy Bowers Cordalis shares her family’s decades-long fight to remove the dams and restore the Yurok Nation’s rights to the Klamath River.

The book, published in October, is the only record of the legal battle between the U.S. government and the Yurok Nation — the largest tribe in California — by a Yurok Tribe member. Cordalis’ attorney work as general counsel for the Yurok Tribe directly resulted in the removal of all four Klamath River dams in 2024.

She hopes Saturday’s event will be a space for “old friends and new friends to come together and celebrate the world’s largest river restoration project in history that’s happening in our own backyard,” she said to Ashland.news in a phone call.

Expressing her gratitude for the Ashland community, she continued, “So many people here have been very important in my life, to the Klamath River and to members of my family.” Ashland public schools gave her the “foundation to go out into the world and create change.”

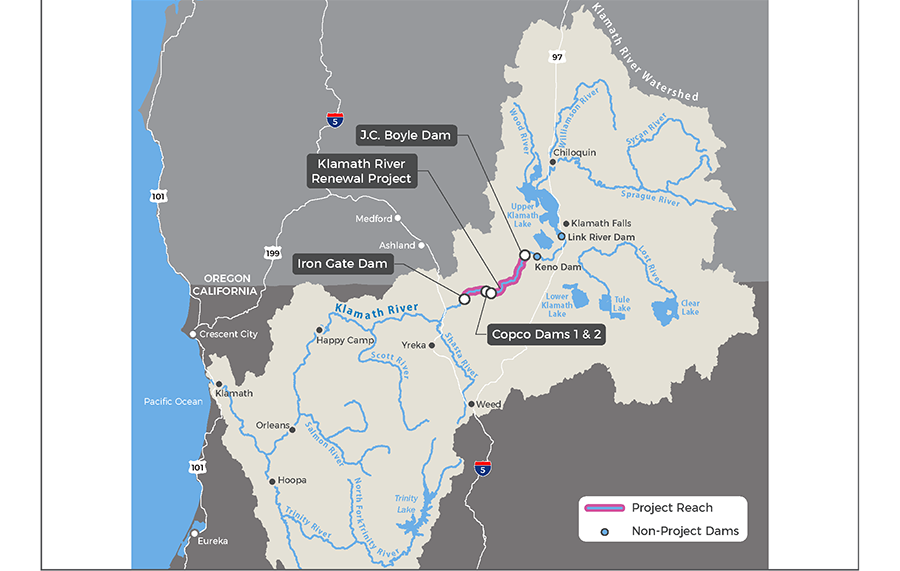

A map of the four removed dams in the Klamath River. The dam removal has already contributed to 30% more salmon in the river, according to Ashland-based Yurok tribe member Amy Bowers Cordalis. Klamath River Renewal Corporation image

The deets

Free indigenous author talk, 3:30 to 5 p.m., Saturday, Jan. 10, Ashland Public Library

The Klamath River, flowing from Southern Oregon to Northern California, and its salmon are the “lifeblood” of the Yurok Nation, who have called the Klamath Basin home for millennia.

“We can’t be Yurok people without salmon and without a healthy Klamath River,” Cordalis said. “We can’t have a healthy river and healthy fish without everybody interacting with it in a good way.”’

Dams and development degraded the Klamath River for generations, diminishing its salmon runs which were once the third largest in the U.S, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries, a federal agency that helps conserve healthy fish habitats.

From around 1910 to 1965, Cordalis said the damage reached its “apex.” The construction of four dams along the Klamath denied fish access to 450 miles of salmon-spawning habitat, resulting in increased water temperatures and toxic algae pollution that killed 70,000 adult salmon, Cordalis explained.

As a University of Oregon student focused on politics and the environment, Cordalis was devastated when she returned home and saw evidence of the largest salmon kill on the banks of the Klamath in 2002. Along with many other indigenous people, it propelled her into action.

“It was a huge catalyzing moment for me. It was an ecological collapse — a completely man-made fish kill,” she said. “My duty as a Yurok person to protect and be a steward was triggered.” She decided to become a lawyer to help the river, reigniting her family’s 170-year battle against the U.S. government.

Another way of life

Among many reasons, she said she wrote her memoir was to share the value of the river, the salmon and of living in balance with the natural world so readers could consider another way of life.

In the book, Cordalis chronicles generations of her family’s struggle, “where she learns that the fight for survival is not only about fishing — it’s about protecting a way of life and the right of a species and river to exist,” the book’s press release says. She writes about her great-uncle’s landmark Supreme Court case reaffirming her tribe’s rights to land, water, fish and sovereignty and her great-grandmother’s protests to end the Salmon Wars, the government’s crackdowns on tribal fishing rights.

Finding out their efforts led to the $500 million dam removal, Cordalis said, “was surreal because you think nothing will ever change. It’s been one of the greatest joys of my whole entire life.”

Witnessing the undamming of the Klamath River made her realize “world renewal is possible,” she said.

The dam removal contributed to 30% more salmon returning this year than last year, according to Cordalis. Fall 2025 marks the one-year anniversary of dam removal and the first time in almost a century that the salmon of the Klamath River will return to a fully free-flowing river to complete their natural run.

Cordalis has received honors from the United Nations, Time Magazine, The National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development for her work and was on the Kelly Clarkson Show in November with her niece Keeya Wiki, one of the teen paddlers who made the first descent of the Klamath this summer.

Formerly a staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund, Cordalis continues to represent the Yurok Tribe as a lawyer and serves as the executive director of the Ridges to Riffles Conservation Indigenous Group, a nonprofit representing Native American tribes in matters like advancing tribal sovereignty, water rights, fisheries and the restoration of the Klamath River.

While raising her kids in Ashland, Cordalis is also working on a children’s book illustrating the story of the river restoration, she told Ashland.news. “The dam removal was really just the beginning,” she said, mentioning various ongoing river restoration projects.

“I hope that this story has the potential to spark a movement — a movement that brings people closer to the earth and to each other, inspiring new approaches to environmental

justice, sustainability, cultural preservation and the role of humans in nature,” Cordalis continued in the press release. “I hope to create a blueprint for hope.”

The free event will feature copies of the book to purchase, courtesy of Bloomsbury Books, as well as a signing after the talk.

“What you do with your life and how you use your life force matters,” she told Ashland.news, encouraging people to do good and not give up hope. “Doing hard things is possible, and creating change is possible. Sometimes it takes multiple generations and decades, but every generation makes a difference. If we keep working collectively and investing in what we believe in, eventually we will get to our goal.”

Email Ashland.news reporter Sydney Seymour at [email protected].

Related stories:

Mongolian scientists visit Klamath River to study world’s largest dam removal and salmon recovery (Oct. 24, 2025)

‘Understand history, create empathy’: OPB Native American boarding school documentary screening set for Klamath Falls this Friday (Oct. 20, 2025)

Feeling of pride, relief for Klamath River paddlers (July 16, 2025)

Kayakers finish 310-mile journey (July 16, 2025)

Indigenous youth call for worldwide dam removal with Klamath River Accord (July 15, 2025)

‘First Descent’ underway: Kayakers following undammed river (June 13, 2025)

First Klamath River descent by tribal youth begins June 12 (June 5, 2025)

Dam removal a success on the Klamath — could Applegate do the same? (Feb. 19, 2025)