Tomi Hazel Vaarde puts the practices of social forestry and permaculture to work in the Little Applegate Canyon

By Debora Gordon

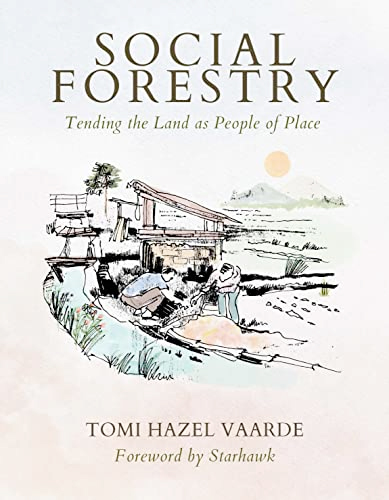

The book “Social Forestry: Tending the Land as People of Place” by Tomi Hazel Vaarde describes how to integrate permaculture, an agricultural system designed to integrate human activity with nature and create a self-sustaining ecosystem through regenerative landscapes. It uses social forestry, a system of management, preservation and protection of forests with the involvement of local communities, aimed at achieving ecological, social and economic benefits.

Describing permaculture in layperson’s terms, Vaarde said, “Ecological landscaping for human inhabitation, including biological elements which cooperate with each other. Soil fertility and resilience.”

Vaarde added, “The social forestry book is very unusual because it’s a work of literature with scientific ambitions.”

The title of Vaarde’s book refers to how “we organize our forestry work on a drainage basis to deliver ecological restoration. The icons we use are beaver, salmon and cultural fire or controlled burning.”

A Quaker and an activist

Vaarde (whose pronouns are “they, them, their”), the author, is a Hicksite Quaker, whose ancestors “go hundreds of years back.” Their first language was Quaker plain speech, which Vaarde describes as “a different form of English.”

Vaarde grew up in South Glens Falls, New York, near Lake George. “My people have been in a set of villages for 400 years in the upper Hudson Valley. We escaped the pogroms in England much earlier.”

Vaarde left their hometown early in life. Their history since includes many political actions. “I’m the only one in my family who left the county. All my family still lives there, an extended family,” which Vaarde puts at more than 10,000, also noting that “Half of the people I went to high school with were my cousins.”

Vietnam War activism

Vaarde said their political activities during the Vietnam War included assisting draft resisters. “We ran the Underground Railroad. I’m out here (on the West Coast) because I’m a political refugee for taking medical supplies to Vietnam. My people (the Hicksite Quakers) did not approve of that. My life was in danger. I had gone through hell during Vietnam as a provider of nonviolent medical supplies. There were no Doctors Without Borders at that time. It was just the Quakers and the Mennonites who were taking medical supplies into Vietnam. I was part of the Canadian left leg, and I ended up on Nixon’s subversives list.”

Vaarde, who has worked on social forestry projects at Southern Oregon’s Wolf Gulch Ranch and the Little Applegate Canyon for 25 years, got started in the field in New York. “We’re organic farmers. And foresters, back in New York,” Vaarde said. “I got a scholarship to go to the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University. I got two degrees — forestry and one in botany, (a) bachelor of science (degree).”

Vaarde moved to the Bay Area in 1969, and soon got involved in the occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay by American Indian activists.

“I ran the blockade to Alcatraz Island with a boat full of supplies under a treaty obligation,” Vaarde said. “The Coast Guard was trying to isolate Alcatraz Island during the occupation, and we used a wooden boat that we had used in Vietnam to bring supplies to Alcatraz Island. We sailed around Angel Island, and we sailed over to Alcatraz and downloaded all our supplies.”

Vaarde describes the decision to relocate to the West Coast because Vaarde felt they were “a political refugee from vigilantes in upstate New York, where I was declared an enemy of the state by fellow students at the College of Forestry and professors at the College of Forestry institutions because I was taking medical supplies into Canada. I was working with the Catholic Workers and the Berrigan brothers and I was on the front lines of the anti-war movement. I was a conscientious objector, right, of draft age at that time. I was a Quaker. I also used to take draft dodgers into Canada with the medical supplies.”

In 1971, Vaarde was hired to teach a course on wild edible plants and woods lore. Among the topics taught were primitive survival skills, organic farming (which was called a biological technology), and engineering with tools and materials.

Introduction to permaculture

“In 1982,” Vaarde said, “I was invited to co-teach the first permaculture course in the Western United States, with Bill Mollison,” an Australian researcher and a developer of the concept of permaculture, at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington.

Mollison “certified me to teach permaculture,” Vaarde said. “I then built the North American permaculture movement. I wrote the standard curriculum, which is used now. I trained the first teachers. I taught them how to do accreditation, because I had an academic background and hardly anyone else did.”

Vaarde’s interests and skills also include music and mountaineering.

“I’m also a folk singer and a poet,” Vaarde said. “I had a folk group with my brothers called the Vaarde Brothers in upstate New York in the early 1960s and we played cafes in upstate New York. I did creative writing at Syracuse University and took a high-level poetry level class. I’m an expert in wilderness survival skills and search and rescue. And I’m a firefighter. I’m a trained fire specialist ….

Fire control vs. controlled fire

“I worked in controlled burns at Crater Lake National Park in the late ’70s and now I am returning cultural fire to the landscape through controlled burning. That’s what I do now, and I make a lot of charcoal at Wolf Gulch Ranch. I was trained in fire control, but I’m now involved in controlled fire, which is different.

“What the city of Ashland did in North America is unique. We’re leaders for returning fire to the landscape, and that’s because of (a memorandum of understanding) we have that goes back to 1929 with the Forest Service. … I was on the Forestry Commission for the city of Ashland during the ’90s and I was involved in the early planning that led to the huge success that we’ve had working with environmentalists and loggers in Ashland.”

Reflecting back on their life’s work and many undertakings, many of which are continuing, Vaarde described themself: “I think I qualify as a social change artist.”

For more information on Vaarde and their social forestry work, visit:

orartswatch.org/a-greater-applegate-creating-community-through-the-culture-of-place

Debora Gordon is a writer, artist, educator and nonviolence activist who recently moved to Ashland from Oakland, California. Email her at [email protected].