At Blue Heron Park in Phoenix, tribal leaders and community members celebrate centuries-old Takelma practices now guiding modern restoration efforts

By Damian Mann for Ashland.news

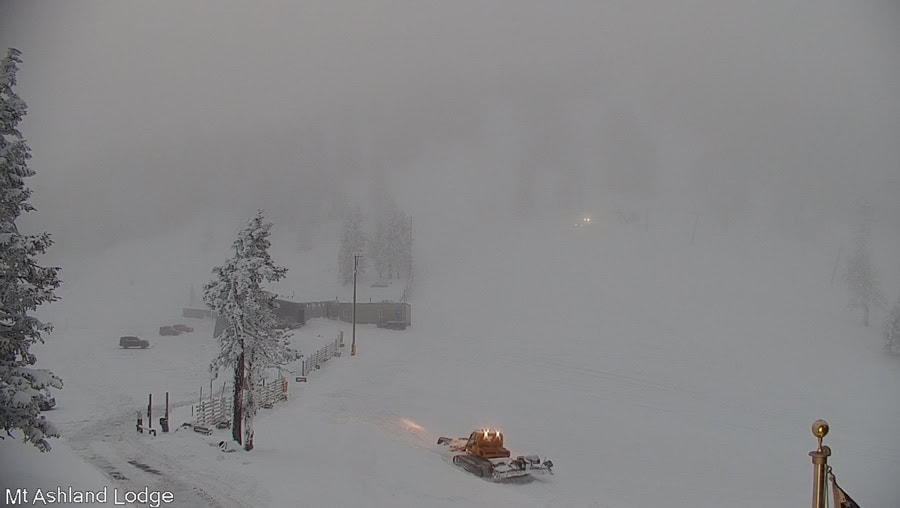

On a frosty Saturday morning at Blue Heron Park in Phoenix, you could close your eyes and almost imagine the Rogue Valley as it was centuries ago when, it’s said, you could walk across Bear Creek on the backs of an abundance of salmon.

Native American songs and drumming filled the misty sky at a public event sponsored by Lomakatsi Restoration Project that celebrated the continuation of land stewardship practices pioneered by Indigenous women.

“Takelma women set fires throughout the Valley,” said David Lewis, an assistant professor at Oregon State University, who has studied the history of Native Americans in Oregon.

Lewis, who has Takelma blood and is a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, said these types of fires were typically lit in late September or October, helping prevent more catastrophic fires and making it easier to find springs, game or travel the valley.

Lomakatsi and other co-hosts of the event, the Ashland Culture of Peace Commission and the Rogue Valley Metaphysical Library, brought together tribal members, elected officials and local residents from the region and beyond.

They celebrated Indigenous history and the continuation of Indigenous forest management practices by Lomakatsi’s inter-tribal youth crew who thin forests in the region.

Based on Lewis’s review of journals and observations from the 1850s, the fires burned off the underbrush, opening up the “prairies” of the Rogue Valley, making it easier to travel and search for herds of animals for hunting.

Lewis went to Washington, D.C., to pore over documents that provided accounts of Native American practices in the valley.

When settlers first came to the Valley, there were a few thousand Indigenous people who lived in villages, which were generally located in the sites where cities that now dot the valley, Lewis said.

For instance, Jacksonville was then known as “Tik’alawyaka.”

The event was also a reminder of how many bands of Native tribes were in the Takelma territories of the Rogue Valley. The Indigenous groups included the Takelma, Hanesakh, Southern Molalla, Nahankhuotana, Taitaniya, Tikalawaya, Athapaskan, Latgawa, Klamath and Northern Shasta tribes.

Lewis told the audience that standing on Takelma lands was a way for him to reconnect with his own culture.

“I want to familiarize myself with the land where my ancestors lived,” he said. “We are part of this place.”

Marko Bey, founder and executive director of Lomakatsi, named after the Hopi term for “life in balance,” applauded the inter-tribal work crew for their efforts.

“Thank you to the people who are working hard on this,” he said. “They’re helping these lands heal.”

The crew planted willow trees during the event to help with the restoration after the devastating 2020 Almeda fire destroyed thousands of homes in Talent and Phoenix.

Lomakatsi lost $2.4 million in federal funding earlier this year, and Bey said after the event that he has been working with tribes and other sources to help his organization develop other funding sources.

Belinda Brown, a member of the Kosealekte Band of the Ajumawi-Atsuge Nation (Pit River Tribe), reminded the audience, “You’re all Indigenous to somewhere. We are all connected.”

Brown said the event honors the inter-tribal youth crew and tribal stewardship of the land.

Dan Wahpepah, from the Anishinaabe, Kickapoo and Sac and Fox tribes, credited much of the forest-thinning work to inter-tribal crews.

“We as native people invest heavily into our youth,” he said.

Wahpepah, who sang an indigenous song to honor the inter-tribal crew, said he celebrated his birthday on Saturday.

“That makes me family with time,” he said. “The way we wake is a prayer for future generations.”

The many other tribal members at the event included Virginia Amoroso of the Ajumawi-Atsuge Nation and Shasta descendant, and Connie McGonagle of the Latgawa Nation and Oglala Lakota descendant.

The event took place in an area that had been devastated by the 2020 Almeda Fire that destroyed thousands of homes and many, many more trees. Now the area is referred to as “Miracle Mile” because the devastation of the fire led to the discovery of 16 natural springs uncovered by the fire in and near Blue Heron Park.

The stark silhouettes of snags leftover from the fire were shrouded in the morning mists behind the stage in Blue Heron Park.

Robert Coffan, with Save the Phoenix Wetlands, held up a bottle of water from the many springs hidden by blackberry bushes and blocked by a large berm on northbound on Highway 99. Now the springs flow into Bear Creek.

“I didn’t discover anything,” Coffan said. “The springs have been here long before any of us humans have been here.”

Oregon Rep. Pam Marsh, D-Ashland, welcomed the spirit of the people gathered at the event and applauded the efforts to restore the land after the devastation of the Almeda Fire.

“We see the results — a creek revitalized,” she said.

She said the fire removed the brambles, and the event itself also remove the brambles that separate people.

Sen. Jeff Golden, D-Ashland, applauded the efforts of Lomakatsi and other volunteers who have helped with restoration efforts

“It never could have happened without all your wonderful work,” he said.

He said he was heartened to see this community effort of people coming together during these “very dark and threatening times.”

Golden noted the event was taking place on a day, Nov. 1, when millions of Americans lost access to food assistance programs because of the federal shutdown.

“It’s not at all clear the path we will be taking,” he said. “It’s essential that we come out and declare ourselves.”

Phoenix Mayor Al Muelhoefer said that for generations and generations before the 1800s, this was indigenous land that provided abundant resources.

“You could literally walk across salmon on Bear Creek,” he said.

David Wick, executive director of the Ashland Culture of Peace Commission, said the event also marked a movement to create an Oregon Peace Trail.

“Peace is an expression,” he said. “Peace is a choice. Peace is action.”

Irene Kai, who moved to New York from China when she was 15 and is co-founder of the Peace Commission, said, “I am really honored to be here today.”

After she first saw a World Peace Flame in Wales in 2015, she embarked on an effort to bring one to Ashland where, thanks to the efforts of her and others with the sanction of the World Peace Flame Foundation, it was lit three years later on the Southern Oregon University campus.

She said the flame honors the native Indigenous culture and also honors Chinese immigrants.

Other organizations involved in the event include the Phoenix Art & Culture Council, Save the Phoenix Wetlands, Rogue River Watershed Council, Red Earth Descendants, and the Inter-Tribal Ecosystem Restoration Partnership.

Reach freelance writer Damian Mann at dmannnews@gmail.com.

Related story: An ‘outdoor classroom’: Activities Saturday in Phoenix kick off Native American Heritage Month (Oct. 27, 2025)