Does refusing to return our lands mean they are merely exercises in wokeness and virtue signaling?

Land acknowledgments, reminders that Native American tribes were forcibly removed from the area, have become common at some entertainment venues nationwide, including the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and SOU. This column by Relocations writer Herbert Rothschild and a letter to the editor by Dennis Kendig look at land acknowledgments from different viewpoints.

By Herbert Rothschild

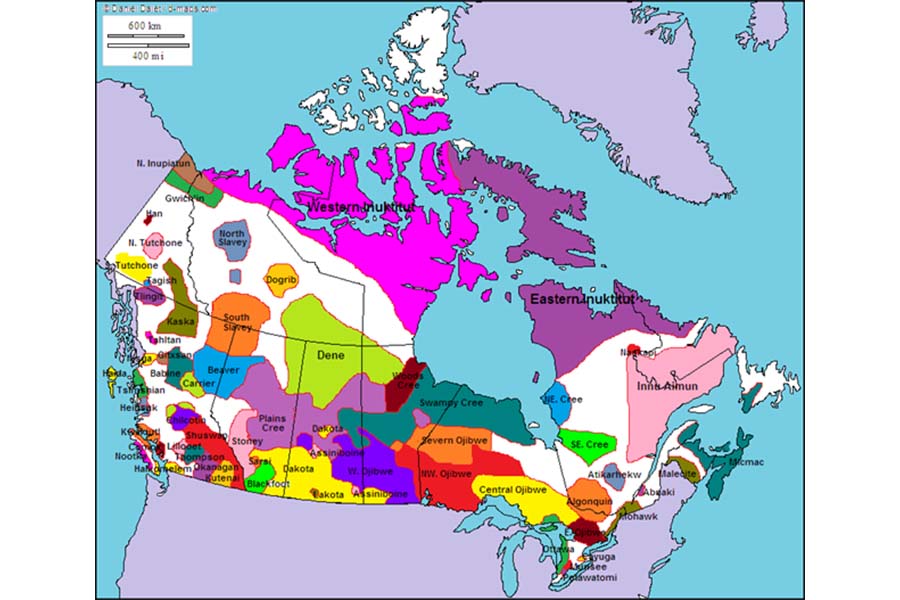

Most people in British Columbia probably used to sit through the recital of land acknowledgments the same way most of us do. If we pay attention at all, they remind us of the grave injustices that First Nations (as they are called in Canada) suffered at the hands of European settlers. But after the ruling in Cowichan Tribes v. Canada last Aug. 7, our neighbors north of the border must be listening to them with alarm.

That case took 11 years, and the trial itself lasted 513 days. At its conclusion, the judge ruled that the Cowichans’ claim to about 1,846 acres of land located within the city of Richmond was valid. The acreage is presently owned by the federal Crown, the city of Richmond, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority and private parties.

The ruling will be appealed, and it’s not clear that the tribe wants to expel the present owners. It says it doesn’t; it wants to vindicate its right to land it occupied in the 19th century and to fish for food in the south arm of the Fraser River. Nonetheless, property values in the disputed area have fallen drastically, and the ruling sent shock waves throughout the province. Its implications for all Canada are uncertain.

An opposing view:

Land acknowledgments are simply moral exhibitionism, writes Dennis Kendig.

The judge’s finding was based on specific legislation that British Columbia had passed. She said that the province’s Land Title Act couldn’t shield the current owners from the tribe’s claims because the province had enacted what it called the Interpretation Act, which prevents the courts from interpreting laws in ways that diminish “Aboriginal” claims. She also said that doing so in this case would conflict with the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which the province had incorporated into its own law by passing the 2019 Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

Neither the U.S. nor any of our states has adopted similar legislation. And with the example of Cowichan Tribes v. Canada before us, it’s inconceivable that we will. Fee simple ownership, a concept alien to Indigenous culture, will not be abrogated here. Still, the case challenges us to think harder about our land acknowledgments than I suspect most of us have done.

I’ve been tempted at times to treat them with scorn. I’ve said to myself, “SOU and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival aren’t about to hand their lands over to the Shasta, Takelma and Latgawa peoples who, they tell us, have a historical claim to it. So, what’s the point of acknowledging their prior occupancy?” The jaundiced answer is that they’re just trying to make themselves feel good, maybe even morally superior. It’s a case of “woke” culture at its worst. No wonder politicians like President Donald Trump and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis got significant mileage out of trashing it.

That jaundiced response, however, isn’t a fair one. I know that’s true when I call to mind SOU’s vibrant Native American Studies program and OSF’s staging of plays that dramatize such historical injustices as the Indian boarding schools. There’s a different way to understand the land acknowledgments and, indeed, all acknowledgments of past wrongs, personal and collective.

Their purposes are to recognize what happened, to understand their consequences, and to make sure there are no repetitions. Because what Faulkner wrote is true: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

The land acknowledgments may seem to reference events that took place in the distant past, but the injustices didn’t end when Native Americans were confined to reservations. Forcibly taking Native children from the reservations and putting them in the notorious boarding schools, whose purpose was to eradicate their identity, began early in the 19th century and didn’t end until 1969. Remains of dead children are still being excavated at some of the sites. Many survivors are alive, and the trauma is intergenerational.

And Native lands are still under attack. Ignoring Native claims whenever there are valuable minerals to be extracted from them is an old story. Uranium mining on many reservations left mountains of tailings that continue to emit low-level radiation. It’s also a current story. To take only one example, the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine in Nevada is under construction on 18,000 acres of ancestral lands of the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone peoples.

Those who wish to sanitize our history in the name of national pride tend to be the very ones who are perpetrating the present harms. For example, after the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Republican legislators moved quickly to suppress once again Black participation in elections.

We needn’t feel hypocritical that we support land acknowledgments even though we aren’t willing to surrender our land to tribes that occupied it in the 19th century. We can regard the acknowledgments as calls to work for justice in the present — for example, lobbying Congress to pass the bill establishing the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States, and opposing mining on Native lands without Native consent.

Still, it would be well for those organizations using the land acknowledgments to realize that, as currently written, they can and do give rise to the jaundiced response I offered above. Their wording should explicitly indicate that they are a call to responsibility in the present, not guilt for the past. And all those organizations should be sure they are shouldering that responsibility.

* * *

Updating an earlier column: Avelo Airlines was the only commercial carrier that contracted with ICE to fly its detainees to holding facilities and prisons. So, it became a target for protests, including one at the Medford airport, which for a time Avelo served with flights to Burbank, California. On Jan. 6, Avelo announced that it will end all flights for ICE. Avelo spokesperson Courtney Goff said, “The program provided short-term benefits but ultimately did not deliver enough consistent and predictable revenue to overcome its operational complexity and costs.” That explanation was a face-saver. The protests forced Avelo to cancel all its West Coast and North Carolina flights and hurt its business elsewhere. Grassroots activism works.

Herbert Rothschild’s columns appear Fridays. Opinions expressed in these columns represent the author’s views. Email Rothschild at [email protected]. Email letters to the editor and Viewpoint submissions to [email protected].