His church supported him when he called out injustice . . . until he called out injustice in the church

By Herbert Rothschild

As word reaches me with increasing frequency of the deaths of people I knew, I feel the urge to reconnect with friends from the past. So it was that, when I was rummaging through a desk drawer and found Roy Bourgeois’ business card, I decided to call him. Luckily, the number was still good, and we talked last Friday.

Roy and I were born within a year of each other in Louisiana, but we grew up in very different worlds and didn’t get to know each other until the early 1980s. Roy came from Lutcher, a small town 40 miles upriver from New Orleans. His family was Catholic and, as his name suggests, Cajun. He went to college in Lafayette, the heart of Cajun country.

Our paths began to converge, however, when Roy joined the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, a foreign missionary order. He had served in Vietnam, thinking he was doing his patriotic duty, but his experience disabused him of his faith in a secular god. He decided to serve a different deity.

Roy’s first posting after ordination as a priest was to Bolivia. At the time it was under the dictatorship of Hugo Banzer, who had come to power in a 1971 coup. He arrested, tortured, exiled and killed labor leaders, indigenous groups, clergymen, students.

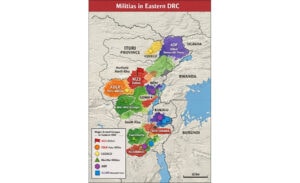

In 1956, Banzer had trained at the Army’s School of the Americas, then located in Panama. At the SOA military officers from Latin America were taught how to repress popular insurgencies in their countries. Its alumni include some of the hemisphere’s most notorious leaders and their generals. The SOA was to become the major focus of Roy’s activism for 25 years.

On March 24, 1980, Oscar Romero, archbishop of San Salvador, was assassinated while celebrating Mass. El Salvador was then in the grip of the Nationalist Republican Alliance, or Arena party, led by Roberto D’Aubuisson. He, too, had trained at the SOA. Just before his murder, Romero had appealed to the military to end its reign of terror. It didn’t, and the U.S. kept sending weapons.

Roy had returned to the U.S. after Banzer expelled him in 1975. Romero’s assassination induced Roy to visit El Salvador to witness the repression firsthand. While there, he had a chance to go into the mountains with the insurgents. He left a note for his hosts, but it wasn’t found, and for several days it was feared that he had been “disappeared.” His name was all over the news.

One focus of the peace group I had founded in 1978 in Baton Rouge was Central American solidarity. So, after Roy got back from El Salvador, I arranged for him to come speak at Louisiana State University. Several hundred people attended, unusual for a campus that was not, on the whole, politically engaged. That was the occasion on which Roy and I first met. Subsequently, I arranged for him to speak twice more, once in Houston, the second time in Ashland, at the Peace House awards dinner in 2016.

One night in 1983, Roy and two others entered the U.S. Army base at Fort Benning and climbed a tree near the barracks housing military personnel from El Salvador. Using a boom box, they broadcast the speech Romero had given to the Salvadoran military just before he was gunned down. Roy was arrested and served 13 months in prison.

During the 1980s he lived in a Catholic Worker house in Chicago and began educating the public about the SOA and calling for its closure. In 1989, six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter were murdered in El Salvador by a squad that included several SOA graduates. Roy decided to intensify his efforts.

By that time the Panama government had expelled the school. The Army had reopened it on the grounds of Fort Benning, a large infantry base in Columbus, Georgia. Roy rented a small apartment just outside the base and founded the School of the Americas Watch.

Roy’s religious order and U.S. Catholics generally supported the SOAW’s work. A major feature was its annual remembrance of people murdered by SOA graduates. It was held outside the base on a weekend in November. Year by year, the number of attendees grew, at its peak exceeding 20,000. A large percentage were young people from Catholic high schools and colleges.

I attended in 1998 and 1999. The second year, I entered the base with hundreds of others and got arrested, although we weren’t jailed or prosecuted. Over the years, however, some 240 people did serve time, including Roy again in 1997, this time for 16 months.

In 2001, the Army felt it had to respond to the pressure SOAW was exerting. So, it changed the name to the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation and purportedly its mission. It insisted that its curriculum stressed human rights. Certainly! Human rights are what U.S. policy in Latin America is all about. The work of the SOAW continued.

Then, in 2008, Roy decided that he could no longer remain silent about the discrimination against women in his own church. He knew too many women of deep devotion and courage — like Maura Clarke and Ita Ford, the two Maryknoll sisters who had been raped and murdered in El Salvador in 1980 — to countenance the prohibition against their attaining full status.

Roy’s presence at an unsanctioned ordination of a woman that March led to his expulsion from the priesthood and the Maryknoll order. It spelled the end of SOAW activity at Fort Benning, although not the end of the organization. And it meant that Roy lost his second family, in which he had lived longer than his birth family. (To hear him speak about his decision and its consequences, view his interview on the Chris Hedges Report.)

Roy still lives in that small apartment outside Fort Benning. His time now is spent more in reading and contemplation than activism. He’s still in pain, but our conversation wasn’t maudlin. Some of our shared memories evoked laughter. I felt good after we hung up.

Although the future seems bleak, I don’t wish to take refuge in the past. Having shared much of my life with people of irreducible decency encourages me to welcome the joys and sorrows to come.

Herbert Rothschild’s columns appear Fridays. Opinions expressed in them represent the author’s views. Email Rothschild at [email protected]. Email letters to the editor and Viewpoint submissions to [email protected].