‘A House of Dynamite’ underscores how flawed are our defenses and our decision-making

By Herbert Rothschild

I was in my second year of graduate school on Oct. 22, 1962, when President John F. Kennedy announced the discovery of Soviet missile sites in Cuba and declared a naval “quarantine” of Cuba. Soviet ships carrying missiles were heading toward Cuba, and for two days — until the Soviet ships altered course — we didn’t know whether there would be a confrontation on the high seas and the start of World War III.

I was frightened. I remember being in Harvard Yard when I heard a military aircraft roaring overhead. I said to myself, “This is it.”

My parents were in town then, and my mother said that my fear was unfounded. I understand her reluctance to believe that we were on the brink of nuclear annihilation, because it’s almost unbelievable that the human race could do that to itself. But Mother was wrong and I was right.

Just how right wasn’t fully revealed until the Cuban Missile Crisis Havana conference in October 2002, sponsored by the nongovernmental National Security Archive, Brown University and the Cuban government. By then, Soviet archival materials had been declassified, and we learned that a single person’s decision had averted utter catastrophe.

What happened was this: At the height of the crisis, U.S. warships fired warning explosives near a Soviet submarine submerged near Cuba to force it to surface. The sub was armed with a nuclear-tipped torpedo. Its officers weren’t in contact with Soviet military command and didn’t know whether war had begun. Because they thought their sub was under attack, it seemed likely that it had. In this condition of uncertainty, they had to decide whether to launch that torpedo at a U.S. ship.

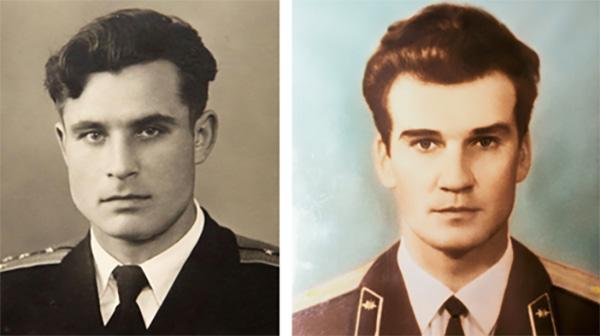

All three officers — the captain, the political officer and the executive officer — had to agree to launch the torpedo. Two of them wanted to. Vasily Arkhipov, the executive officer, wouldn’t agree. When Arkhipov died in 1998, his name was virtually unknown. After the 2002 conference, what he had done was recognized. In 2017, Russia awarded him posthumously its first “Future of Life Award,” which recognizes exceptional measures, often performed despite personal risk and without obvious reward, to safeguard the collective future of humanity. Still, my guess is that most of my readers are hearing Arkhipov’s name for the first time.

Since 1962, meaningful safeguards have been put into place, such as the White House-Kremlin hotline, to reduce the chances of finding ourselves in a similar situation. Those safeguards, however, are paltry compared with the complexity of the challenge and the consequences of failure. It’s simply inexcusable that people in the nuclear states — especially people in the U.S., which has been committed to nuclear weapons since their creation at Los Alamos, New Mexico, in 1945 — have allowed our leaders to perpetuate the possibility of a nuclear holocaust.

These memories and feelings, especially fear and anger, were evoked last week when I viewed the Netflix film “A House of Dynamite.” If you have made no effort to end the intolerable danger to which administration after administration has exposed us, the very least you ought to do is take 112 minutes and view the film. It will shatter your complacency.

The characters in the film are fictional, but Noah Oppenheim, the scriptwriter, worked hard to present factually the ways in which our country has prepared itself for a nuclear attack. His achievement has gotten high marks from the Arms Control Association, Defense One, and people who have worked in U.S. Strategic Command and the White House Situation Room.

Two aspects of our preparation are key — destroying ICBMs before their nuclear warheads separate from the delivery vehicles, and the processes and protocols for deciding whether to retaliate and thus inaugurate a global catastrophe. I’m going to discuss both apart from what information the film provides.

Since President Ronald Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative, the U.S. has spent between $250 billion and $400 billion (in inflation-adjusted dollars) to build a missile defense system. As many experts said from the start, this has been a fool’s errand. After more than four decades, even the U.S. Missile Defense Agency claims no more than a 57% success rate for the 21 flight tests it says it has conducted on its ground-based interceptors, or GBIs.

Further, the tests don’t faithfully approximate real conditions. The launch time, location and trajectory of the incoming test missile are known in advance, and there are few decoys used with it. So, when the film shows the failure of the GBIs launched from a base in Alaska to stop a single missile, that isn’t a factual misrepresentation. And were there an attack by hundreds of missiles amidst thousands strips of aluminum “chaff” as decoys, the chances of intercepting even a small fraction of them are next to nil. Still, we keep at it.

The other aspect is the decision-making. What the film shows is how, under intolerable time pressure (less than 30 minutes before the warhead will strike), there is confusion and uncertainty. It’s a challenge to locate and position all the key people. More difficult is accessing the necessary information about the origin of the attack and whether it’s a prelude to a much larger attack. Then, there’s the matter of whether other nuclear powers, which may be struggling with uncertainty about who we might strike in retaliation, may launch preemptively.

None of that is fictional. The many former watch officers and senior staff who were interviewed by major news outlets said that the film’s depiction of the frantic pace, overlapping calls, and layering of information are accurate. The president, who has the final say in whether to retaliate and on what nation(s) and to what extent, simply cannot know whether he is right — and getting it right may itself be suicidal.

In sum, we aren’t that far beyond where those Russian submarine officers were in 1962. What else can we conclude but that nuclear policy simply mustn’t be left in the hands of the warmakers? Either we give peace a chance or we continue to chance self-immolation.

Have you contacted President Donald Trump yet and asked him to accept Russian President Vladimir Putin’s offer to observe the limits on offensive nuclear weapons in the New START treaty for a year beyond its expiration on Feb. 5. If not, what the hell are you waiting for?

Herbert Rothschild’s columns appear Fridays. Opinions expressed in them represent the author’s views. Email Rothschild at [email protected]. Email letters to the editor and Viewpoint submissions to [email protected].