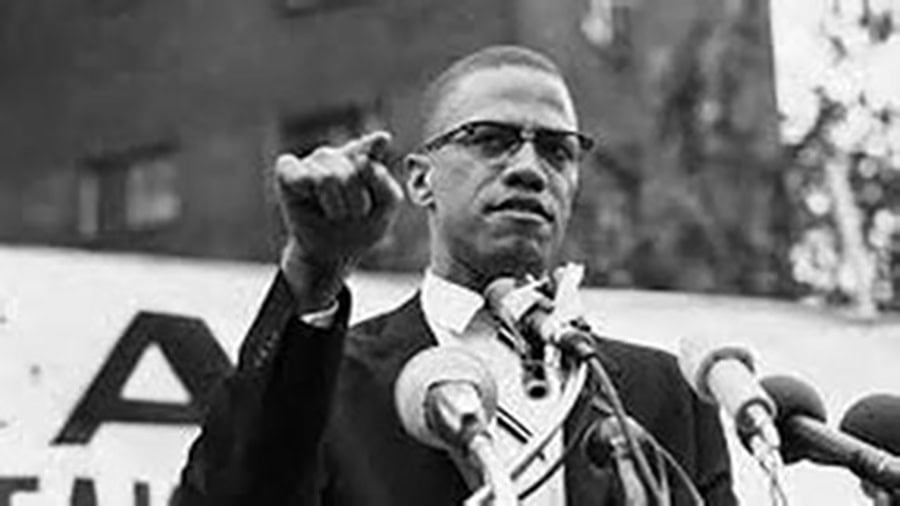

His understandings, especially about human dignity, were developing rapidly when he was murdered

By Herbert Rothschild

Tomorrow, Feb. 21, is the anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X. When he died, it may have been a greater loss to our country than when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at the same age of 39 some three years later. Not because Malcolm was a better person than King or because he had made a larger contribution to the advancement of equality and justice, but because we will never know what further contributions that extraordinary man would have made.

As King wrote in the New York Amsterdam News three weeks later, “Malcolm was still turning and growing at the time of his brutal and meaningless assassination. . . . Like the murder of Lumumba (Patrice Lumumba, first prime minister of an independent Congo), the murder of Malcolm X deprives the world of a potentially great leader. I could not agree with either of these men, but I could see in them a capacity for leadership which I could respect, and which was just beginning to mature in judgment and statesmanship.”

When he died on April 4, 1968, King was mature in judgment and statesmanship. He wasn’t the founder of the nonviolent movement that ended Jim Crow — people like Bayard Rustin have a stronger claim. But beginning with the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955-56, King became the national face of the movement. He was its most important liaison to the White House during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations — whose support was critical — and his was the inimitable voice that persuaded most Americans to deem racial bigotry morally indefensible.

Had he lived, King undoubtedly would have achieved more, especially because in 1967 he had refocused on economic injustice and its connection to U.S. militarism, a struggle that more than ever needs all the champions it can get. Nonetheless, as he said in a speech on the night before his murder, “I’ve been to the mountaintop.”

King’s primary demand was for justice. Malcolm’s primary demand was for respect. A reader of Malcolm’s autobiography becomes acquainted with a person who struggles to affirm his own worth in close conjunction with his assertion of the worth of all Black people. And because, in our country, that struggle is inescapably conducted in relation to white people, we follow his effort to get beyond the perceived need to affirm Black dignity by denying it to whites. That was one reason for his break with the Nation of Islam.

Unlike Malcolm, King appeared to have no need to assert his human worth. He presumed it, and the source of his personal security was the faith nurtured in the Black church. That was true of the thousands of Southern Black people who braved the rage of whites, and the contrast between their bearing and that of their antagonists is unmistakably apparent in every photograph and film clip of those encounters. Southern Blacks had no need to denigrate whites; whites were eager to do that to themselves in defense of white superiority. When they stopped doing it, the relationship between members of the two races had a reasonable chance to get on a proper footing.

Mutual respect is impossible without self-respect. To require others to apologize for, or even defend, their identity is to declare that one has no interest in a proper relationship, only dominance.

The “Black savage” of the unreconstructed Southern mind has no currency now except in the extremist groups that the Southern Poverty Law Center keeps tabs on and, apparently, in the White House. I’m not sure the same is true of the “white devil” of Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam. Current Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan still asserts that the Yacub myth of white creation is factual. More common, though, is an implied demand that whites not just apologize for what we’ve done, but also for who we are, as if the doing and the being are inextricable.

That this demand arose isn’t surprising. According to George Christian, President Lyndon Johnson’s press secretary, Johnson said to him after the urban riots sparked by King’s assassination, “I don’t know why we’re so surprised. When you put your foot on a man’s neck and hold him down 300 years, and then you let him up, what’s he going to do? He’s going to knock your block off.” Nonetheless, it’s a demand to which whites must not accede.

Those most likely to accede to that demand are those of us most cognizant of what we have done and most willing to make amends. White liberals are the target readiest to hand. We are the ones likely to agree with generalizations to which we shouldn’t. Years ago I was in an antiracism workshop that began with the undiscussable proposition that racism is a pathology peculiar to white people. In a low key I demurred, but that was the only pushback.

In a 1953 essay titled “Stranger in the Village,” James Baldwin wrote that the Black man “is not a visitor to the West, but a citizen there, an American; as American as the Americans who despise him, the Americans who fear him, the Americans who love him — the Americans who became less than themselves, or rose to be greater than themselves, by virtue of the fact that the challenge he represented was inescapable. . . . His survival depended, and his development depends, on his ability to turn his peculiar status in the Western world to his own advantage and, it may be, to the very great advantage of that world.”

I’m sorry that Malcolm didn’t live long enough to advance that work further than he already had.

Correction: It was pointed out to me that the Chat GBT-generated map of eastern Congo and adjacent countries that accompanied my column last week incorrectly drew the country boundaries in several ways. The map served its primary purpose — to depict the prevalence of militias in eastern Congo. Still, I dislike giving you incorrect information.

Herbert Rothschild’s columns appear Fridays. Opinions expressed in these columns represent the author’s views. Email Rothschild at [email protected]. Email letters to the editor and Viewpoint submissions to [email protected].