OSF school visits, a tradition started by founder Angus Bowmer, take the Bard to young people to inspire the next generation of playgoers

By Jim Flint

On a school day, in a room built for pep rallies or physical education classes, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival can turn a gymnasium into a theater.

Teaching artists arrive early, set up, and then — without the protective distance of a proscenium arch — begin speaking words written centuries ago, asking students not only to follow a story but to enter it. The performance itself is short: about 40 minutes. What follows is just as important: a talkback, questions and a workshop that asks bodies to move and voices to try language out loud.

For some students, it’s the first time they have ever seen live actors. For others, it’s the first time Shakespeare stops being a unit in a textbook and becomes a living exchange.

OSF calls it the School Visit Program. But in practice, it functions as something larger: a traveling version of the festival’s identity, an attempt to make theater not only a destination in Ashland, but a presence in classrooms and communities that might never make the trip to Southern Oregon.

Although many large regional theaters host students on their own campuses, only a few maintain educational outreach programs like OSF’s because of the high cost of school visits. On the West Coast, 5th Avenue Theatre in Seattle, Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles and Oregon Children’s Theatre in Portland have similarly robust touring programs.

The key differences: OSF is rare because it actively seeks out small, remote communities that lack their own drama programs, often requiring the teams to travel with their own props and minimal tech support. And the program is distinguished by its decades-long history and massive range. It currently deploys teams throughout the American West.

At the center of OSF’s education work is an old question that never fully disappears: Is this outreach mission-driven, audience-building or both?

The answer — heard across interviews with OSF leadership, educators, students and longtime company members — is that it is all of those things at once. Education is institutional legacy, artistic ecosystem, equity effort and, in a time of financial pressure on regional theaters, strategic investment.

“Inspiring the next generation and engaging our elders, who are lifelong learners, is at the heart of all we do at OSF,” said Artistic Director Tim Bond. “Festival founder Angus Bowmer was an educator and so it has been the heart of OSF since the beginning.”

Education from the start

Education at OSF didn’t begin as a side program. It grew with the festival itself.

The earliest educational foundation dates to 1949, when the festival launched the Shakespearean Summer School, guided by Stanford professor Margery Bailey, OSF’s academic adviser. In 1953, that work broadened into the Institute of Renaissance Studies, formally incorporated into OSF.

Then, in 1970, Bowmer launched what became the most visible bridge between OSF and the classroom: the School Visit Program, touring performances and workshops brought directly to schools.

Today, OSF describes the program’s origin this way on its website:

“OSF founder Angus Bowmer started this program over 40 years ago with one simple goal: to bring Shakespeare into as many schools as possible. We are proud to continue this legacy that for many students will be their first and sometimes only exposure to theater and Shakespeare’s plays in performance.”

That legacy is not just branding. It shapes internal philosophy and the way the festival talks about why education exists at all.

“All education and engagement work supports the shows on our stages. Without the shows, we would not exist,” said Kirsten Giroux, OSF’s director of education and engagement. “Angus Bowmer, a teacher, hired a director of education in 1948. Learning has always been part of the fabric of OSF. Fulfilling the curiosity of our playgoers is in our DNA.”

Interrupted — then rebuilt

The continuity matters all the more because OSF’s education programs, like so much else in the theater world, were not untouched by the combined shocks of pandemic shutdowns, wildfire smoke and financial crisis.

During the period of 2019 to 2023, OSF underwent severe operational and programmatic interruptions. Performances and educational events were paused or suspended, staffing reduced and organizational planning disrupted. Nataki Garrett, artistic director during that time, resigned in May 2023. Under Bond’s leadership — in the wake of shutdowns and restructuring — OSF began relaunching education programs, including the School Visit Program, in 2024.

Giroux described the rebuild as incremental, shaped by safety realities and by demand from teachers.

“As COVID became less invasive,” she said, “the demand for more events for students came in loud and clear from teachers. So, workshops and tours came back into play.”

Then the work widened outward.

“The next year, we needed to reengage with our adult patrons, so we brought back adult classes,” Giroux said. “This year we will have some community engagement. Each year we add something. It has been pretty clear what has needed to happen again as we began rebuilding.”

Where education lives now

Today, OSF places its education and outreach inside an “Engage & Learn” framework, programming that runs in parallel with mainstage productions and is designed to deepen a visitor’s relationship with the plays and with theater itself.

The festival encourages students, teachers, and patrons to build layered experiences around productions: prefaces, behind-the-curtain talks and tours, group discussions, workshops, talkbacks and study guides. OSF’s website frames these experiences as “invitations.”

OSF’s larger educational philosophy is explicit: to inspire a lifelong relationship to theater.

Taking theater to schools

The School Visit Program is OSF’s most direct outreach mechanism: a touring program that brings the festival into schools.

This season, OSF offers two touring performance options:

Shakespeare: “Hamlet” — a “fast-moving 40-minute version of the classic” designed as an introduction to Shakespeare’s most studied tragedy.

Literature: “Boo!” — a 40-minute collage of stories, poems and scenes, mixing Shakespeare and Emily Dickinson with modern voices like Khalisa Rae and Harlan Ellison.

Workshops are built into the same touring framework. For 2026, the workshop offering is titled “Tell Me a Story!” and is designed to get students to “engage with text kinesthetically,” the website says.

The structure is designed for scale. A single day of school visit programming can include up to four events: performances plus talkbacks, and either one two-hour workshop or up to three one-hour workshops. Performances can be scheduled for groups of 25 to 500 students, and workshops are limited to 40 students.

The cost: $1,500 per day, with partial scholarships available. That structure makes the School Visit Program both accessible and limited. It is built to reach many students at once, but it also depends on scheduling, funding and an infrastructure that must function across wide distances.

Tara Houston, OSF’s senior coordinator of education and engagement, described the scheduling pipeline from first inquiry to tour day.

“To request a visit, teachers complete a form with details such as their school location, available dates and scheduling restrictions,” she said. “Once I receive the form, I reach out to confirm information and provide our scholarship application if requested.”

Then comes the routing puzzle.

“Registrations open in November and close in the spring,” Houston said. “After interested schools have submitted requests, I build a route for our teams that stops at each location and share a preliminary schedule around the time schools break for summer.”

The work continues into the school year.

“When school resumes, I reconnect with teachers to ensure our scheduled dates still work,” Houston said. “That’s when we begin planning the visit’s schedule — how many performances and workshops they’d like and the sequence of the day’s events. Daily schedules are finalized as our performers begin rehearsals.”

And behind the scenes, OSF builds the materials that make the program legible to students and teachers: study guides, publicity packets, posters, images, performance programs and support for teaching artists as they move from rehearsal to classroom.

“After each visit, teaching artists complete summary forms reflecting on their experience, and I send post-visit feedback forms to teachers to gather their insights,” Houston said.

When schools come to OSF

For schools that travel to Ashland, OSF offers an experience that can be built like a curriculum: shows, prefaces, workshops, tours, talkbacks, and group discussions — designed to help students engage with what they are seeing.

Workshops are typically 90 minutes and are tailored to a group’s needs. Group pricing is structured to encourage larger participation: $15 per ticket for 15 to 29 students, $12 per ticket for 30 to 59 students, and $9 per ticket for 60 or more students.

For teachers, the menu matters because it makes the visit more than a matinee. It becomes preparation, context, reflection and — ideally — conversation that continues long after the bus leaves town.

Blair Cromwell-Fawcett, a theater teacher at Dallas (Oregon) High School, described why prefaces and supporting events matter for her students.

“I always book a preface where I can because having students understand key talking points in the plot, the director’s and designer’s visions, and exposure to some of the language in the play deepen their understanding,” she said.

She described how talkbacks can shift a student’s relationship to plays that emerge from worlds outside their own experience. Those 2025 plays were “Fat Ham” and “Jitney.”

“We booked a preface for both and were also able to sit in the talkback for “Jitney” following the show,” she said. “They were able to learn about the social, political and economic events that swirl through those stories. That made it possible for them to begin to understand and empathize with the characters in a way that would not have been possible if we had simply bought a ticket to see the show.”

She measures the impact by what she hears months later.

“This year, we went to see “Primary Trust” at Portland Center Stage and within the conversations students were having about that play, I could hear the seeds that had been planted so many months ago in their experiences at OSF,” she said.

Learning through the body

OSF’s approach to Shakespeare education is rooted in a belief that comprehension is not purely intellectual — it is embodied.

“Our philosophy of teaching Shakespeare’s works has developed over many years and has always landed on exploring the language in a full-bodied way,” Giroux said. “Sometimes approaches to learning, understanding and enjoying Shakespeare’s plays have been very intellectual and head-centered. But the truth is, we understand language with our whole body.”

That philosophy shapes workshop design and the way teaching artists adapt Shakespeare for contemporary classrooms.

Houston described what “embodied and kinesthetic learning” looks like in practice.

“Workshops require an open space where learners can move,” she said. “Depending on the lesson, students may read aloud, walk at varying speeds, or speak words as though blowing bubbles.”

She described the core tools utilized in the process.

“Activities often involve repetition, movement, and creative play — snapping, stomping or enacting meaning through gestures,” Houston said. “That builds understanding, starting with simpler exercises and moving to more complex interactions with text.”

That method is also about access — lowering the barrier for students who arrive thinking Shakespeare is for other people.

“Live performance and Shakespeare can feel intimidating,” Houston said. “Nearly half of our audiences are first-time visitors, many of whom have never seen a live production before.”

She described OSF’s job as making theater legible as a shared human act.

“Despite the challenge of understanding 17th-century language, the circumstances characters encounter are profoundly human: falling in love, grappling with leadership and finding one’s place in the world,” she said.

She described the practical role of prefaces, talkbacks, workshops and study guides as moving students from passivity to participation.

“Many first-time theatergoers worry that they’re not ready, smart enough or ‘fancy’ enough to understand and enjoy live theater,” she said. “We believe our work is for everyone.”

What students take away

If OSF’s educational philosophy is built on access and embodied learning, its success shows up in the language students use to describe their experience afterward — how they remember it and what changes.

Grace Kinzie, a Dallas High School senior, said her first surprise was that the festival didn’t feel daunting.

“I think I expected it to be more of a maze than it was,” she said. “But really it’s not too much for the senses and it ended up being really easy to traverse.”

She noted how easily she settled into the experience.

“I was surprised how comfortable I felt watching the shows,” she said. “That sounds odd, but it wasn’t overwhelming. I just felt at home and I was able to feel like I was in those worlds with those people.”

One moment during a performance struck a particularly personal chord.

“I had moments of extreme nostalgia when watching “Macbeth” in 2024,” she said. “’Macbeth’ was my very first high school theater production and so the show is quite special for me.”

And she described the broader impact on her sense of theater as a profession and a future.

“I think my experiences at OSF have shown me that the theater magic continues outside of the bubble of high school,” she said. “I can see how much those actors and technicians enjoy their work and how passionate they are.”

For Robert Thomas, an eighth-grader at North Middle School in Grants Pass, the experience was an eye-opener — an introduction to the craft and scale of professional theater.

“What surprised me when we got there is how nice the set was and how big and detailed everything was,” he said.

His direct contact with theater technology was also memorable.

“Another really cool thing we saw was some of the tech equipment, being able to see it and touch and use it was so amazing,” he said. “I hope that one day I can join that team and work with them,” he said. “I will be on that OSF stage one day, and it all started with this one trip!”

The hinge point: teachers

Teachers stand at the hinge point of OSF’s educational ecosystem. They are planners, fundraisers, chaperones, curriculum builders and the first audience for how students change afterward.

Jennifer Lynde, a theater director at North Middle School in Grants Pass, described how her students responded to OSF as an encounter with professional excellence.

“When we went to the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, what stood out to me the most with my students was how seriously they all took it,” she said. “They really understood the great opportunity they were given and didn’t take it for granted.”

In describing their first impressions, she notes that, upon arrival, students were “awe-stricken” by the beauty of the campus and the theaters.

During a backstage tour, “they were very attentive,” she said. “You knew just by looking at their expressions it was something they were going to remember for the rest of their lives.”

Live theater has a special impact on students, she said.

“Seeing a live production is much more powerful than reading out of a textbook. When you see a live performance, you are seeing someone show emotions physically, vocally and right in front of you.”

Dallas High School’s Cromwell-Fawcett sees OSF’s impact as partly artistic, partly sociological, exposing students to new worlds and contexts.

“Students from Dallas have no natural way to understand the conflicts and obstacles presented in plays that are outside of their experience,” she explained, noting how contextual support makes those worlds more accessible. “They are able to learn about the social, political, and economic events that swirl through those stories.”

Who gets to come

OSF’s education work has always contained an access promise: The festival comes to schools that cannot come to it, and it builds price structures and scholarships to keep trips possible.

But equity is not only a financial question. It is also about rural distance, transportation, unfamiliar environments and the emotional barriers students carry into the experience.

OSF’s Houston described the impact of the School Visit Program in rural communities.

“Last year we visited a rural farming community for the first time,” she said. “For many of those students, our SVP performance was the first time they’d seen actors live.”

She said the impact became visible later.

“A couple of weeks after our visit, we got the loveliest thank you cards from the school and so many students mentioned how important it was that we came to their community,” Houston said. “And at another school, one student had learned to read only the year before, yet was reading Shakespeare aloud in a workshop.”

Lynde, too, framed access as personal, especially when students feel socially or economically outside the room.

One of her stories centers on a Grants Pass student who struggled to make friends.

“She joined us on the trip and through the different activities you could see her confidence growing,” Lynde said. “On the bus ride home, she told me she wanted to join theater because she found her people. She has been a theater student ever since.”

In another story, Lynde described a student living with extreme economic instability, worried not only about money but about appearing acceptable.

“He told me how he was concerned about attending,” she said, “He was nervous because he didn’t have fancy clothes to wear to make a good impression. He was also on the verge of homelessness,” she said.

What mattered, she said, was how quickly the students felt they belonged.

“He told me the OSF staff was so welcoming and friendly,” Lynde said. He came away feeling accepted rather than judged, and was able to relax into the experience as just another student.

How education shapes the art

The common story about arts education is that it’s altruism: outreach as service. OSF’s leadership makes a different argument. Education is not separate from the art — it shapes the art.

Artistic Director Bond said education and engagement is integral to how OSF imagines and performs work.

“They provide feedback, perspective and energy,” he said. “This shapes our play choices and rehearsal rooms, and informs the way we tell stories. Young audiences help OSF see plays with fresh eyes and new perspectives.”

He also described how student audiences change performance energy in real time.

“Having students in the audience brings a unique energy. Artists notice a different kind of attentiveness and unexpected reactions that can bring light to different aspects of the play,” Bond said.

And he emphasized a structural choice Oregon Shakespeare Festival makes with regard performances students attend.

“A unique aspect to our programming is that student groups are integrated into our adult audiences and into some of the ancillary events,” he said. “Students and patrons of all kinds share the same experience in the theater.”

The economic ripple effect

In Ashland, education outreach is not only a cultural good, it is part of the city’s seasonal economy and its long-term identity as a destination.

The impact on Southern Oregon’s economy from student-teacher tourism and the cultivation of future visitors through the SVP initiatives is not lost on area business leaders. Sandra Slattery, executive director of the Ashland Chamber of Commerce, called student visits historically significant.

“Tourism generated by student groups has always been important to Ashland,” she said, citing increased lodging visits, dining and local shopping.

“And while some focus solely on the benefits of immediate visitation, the real value lies in cultivating lifelong lovers of theater and, of course, our beautiful Ashland,” Slattery said.

When artists meet students

OSF’s education programs also matter because of what they do for artists, giving them access to audiences rarely encountered so directly in regional theater.

Michael Elich, who spent 21 seasons in the OSF company, described his connection mainly through talkbacks.

“It is rare in the regional theater world to have this type of connection with an audience, especially with a group of diverse young students, many with hopes of pursuing a career in the arts themselves,” he said.

“I loved it.”

Linda Alper, a 24-season OSF company actor, placed education at the center of the institution’s value.

“I think the OSF education department is the crown jewel of the theater,” she said.

She connects her own professional growth to what she learned through OSF’s educational outreach programs.

“I both taught and studied with the education department and learned so much from them,” Alper said. “I don’t think I would have won two Fulbrights or would have been able to succeed in my international work without what I learned from OSF education.”

Robynn Rodriguez offered the clearest narrative of legacy: the student inspired by an outreach performance who later became the outreach performer.

When she was a high school junior in 1975, she joined a friend for a trip to Chico, California, to see a play at the city’s Cal State University. They arrived in time to see a special afternoon performance they hadn’t expected.

“I remember seeing two guys in street clothes — actors from a place called the Oregon Shakespeare Festival — giving a seamless, bare-bones performance of monologues, scenes and vignettes from several of Shakespeare’s plays. I had never seen anything like it. I was hooked,” she said.

Years later, on a six-week tour in 1989 as a member of an OSF School Visit Program team that began in Nevada, she experienced the reciprocity of outreach in the field.

“We ended up learning more from the students and teachers we met there than they learned from us,” she said.

She went on to complete 22 seasons as an OSF actor, appearing in more than 40 productions. She has performed internationally and began directing in 2013.

When it becomes personal

Education stories can turn abstract quickly: budgets, instruction, program menus. But the meaning of outreach often lives in one face, one sentence, one moment of recognition.

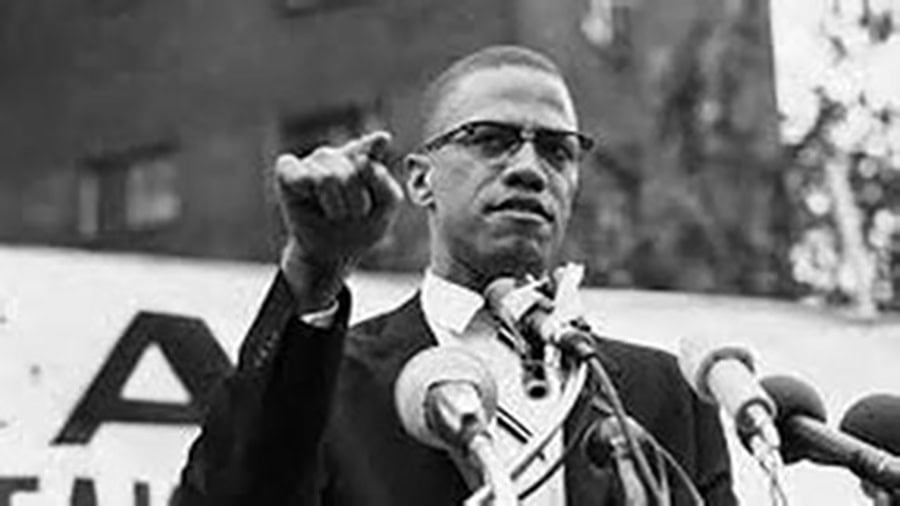

Houston described a tour stop at a school with a large population of Black students where teaching artist Brandon Foxworth performed. She said the teacher reported that “students talked about Brandon for weeks afterward — learning, observing, and feeling seen.”

Foxworth’s own words, shared by Houston, capture what representation can do inside an outreach program.

“It has been a pleasure being able to visit these schools regardless of what things unite us or separate us,” he said, “but to be able to be at a school where students look like me, and may share similar experiences as me, made this school stop the most meaningful part of the tour. It is an active representation of why I am an artist and why I became an artist.”

That’s not marketing language. It’s an artist describing, in real time, why outreach is not separate from art-making.

The long view

Cromwell-Fawcett has taken students to OSF long enough to measure impact beyond the matinee and beyond the curriculum.

“It began with me as fascination and wonder” she said. “My relationship with OSF has become like visiting an old friend.”

She has also watched students expand their sense of what stories — and what worlds — are available to them.

“We are from a community that would never have the appropriate resources to tell the kinds of stories we can see at OSF,” she said. “This increased perspective allows them to see the world in a much larger way and makes the larger world seem closer to them because they have a glimpse of understanding.”

She has watched something else happen, too: the blurring of distance between student and artist, between aspiration and possibility.

“They will have a wonderful time exploring Ashland and even get to see the artists they admire on the streets,” she said. “That matters. To see an artist at a restaurant makes a life in the arts seem more possible. These are real people. And maybe in the future, some of our students can achieve that dream too.”

At OSF, educational outreach is often described as access: bringing Shakespeare to schools, bringing students to Ashland, making the first encounter possible.

But the deeper truth — revealed by students imagining themselves on the OSF stage, by teachers describing confidence and empathy, by artists remembering their own first outreach performance — is that the work is not only about Shakespeare.

It is about belonging.

It is about being welcomed into a cultural space that can feel closed.

It is, in the end, about theater surviving not only as an art form, but as a lived, shared civic experience — one that still begins, again and again, with a hand reaching out.

The 2026 season begins on March 13 and is scheduled to run through Oct. 25. For more information about OSF plays and programs, or to purchase tickets, visit osfashland.org.

This story originally appeared in Oregon ArtsWatch.

Freelance writer Jim Flint is a retired newspaper publisher and editor. Email him at [email protected].