The Ashland resident, whose career took off with ‘Evil Dead’ movies, wrote, directed and stars in ‘Ernie & Emma’

By Jim Flint for Ashland.news

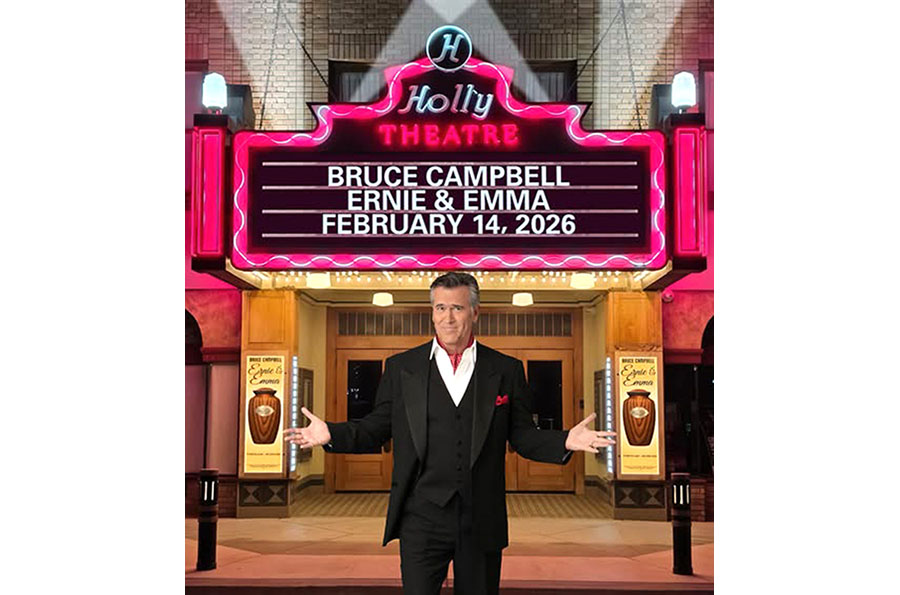

On Valentine’s Day, the red carpet will roll out in downtown Medford, where the historic Holly Theatre will host the world premiere of “Ernie & Emma,” a tender, Oregon-made romantic comedy from cult icon and Ashland resident Bruce Campbell.

Presented in partnership with the Ashland Independent Film Festival, the Feb. 14 event doubles as both a cinematic homecoming and a fundraiser supporting independent film in Southern Oregon.

Doors open at 6:30 p.m. and the film starts at 7:30 p.m. Reserved seat tickets are $23.50 each. You can watch the film’s trailer or purchase tickets at hollytheatre.org. Tickets also will be sold at the door if they’re not sold out.

For Campbell — best known for chainsaw-wielding bravado in “Evil Dead” and its sequels, a genre-bending turn in “Bubba Ho-Tep” and decades of fan-favorite performances — the film marks a striking shift in tone. “Ernie & Emma” is a quiet, character-driven road movie that trades splatter and spectacle for grief, memory, humor and love that lingers after loss.

Independent again

Campbell wrote, directed, produced and stars in the film, which was shot entirely in Southern Oregon with local cast and crew.

“I refer to it as crawling back into the womb, because this is the first time since the original ‘Evil Dead’ where I’ve made a movie entirely outside the studio system,” Campbell said.

“The good part is that you have nothing but creative freedom and can do anything you want within budget constraints. The bad news is, there’s no one to bail you out if you go over budget. The positives still outweigh the negatives tenfold.”

That independence is woven directly into the story. Campbell plays Ernie Tyler, a small-town pear salesman navigating Pear Valley, Oregon, after the death of his wife, Emma. Guided by a meticulous list of instructions she left behind, Ernie embarks on a bittersweet road trip that nudges him — sometimes gently, sometimes stubbornly — toward reckoning with the life he shared and the one still unfolding.

Life and legacy

As Campbell approaches his late 60s, the material reflects a deliberate evolution.

“As I get older, my tastes change and my body changes, so I don’t want to be the guy slinging chainsaws anymore and that subject matter no longer appeals to me,” he said.

“I have a stronger sense of mortality now and it comes in to play. As I get into my golden years, I tend to look back on my life more. The character of Ernie encapsulates elements of my father and myself.”

Rather than presenting grief as a clean arc toward closure, “Ernie & Emma” leans into the accumulated history of long partnership.

“I was mostly interested in exploring what a long-term marriage is actually like,” Campbell said. “If you’re married a long time, a lot of stuff happens — good and bad — and I felt there’s no point hiding the scars that we get along the way.”

Landscape as story

Southern Oregon is not merely a backdrop but a central character in that exploration. The film features recognizable local sites, including Table Rock, the Rogue River, Lithia Park, the Bigfoot Trap near Applegate Lake, and the Ashland Elks Lodge. Campbell believes the region’s geography shapes not just the visuals but the people within it.

“The valley is big part of the story,” he said. “The beauty of a movie without a huge budget is that we do have huge backdrops in Oregon and they inform where Ernie lives. He interacts with his environment, just like we do in the Rogue Valley. Flatlanders behave differently than people with mountains all around.”

Creative partnership

The production was deeply personal. Campbell produced the film alongside his wife and longtime creative partner, Ida Gearon, marking their first fully independent collaboration.

“I bring the heat and Ida brings the cold,” Campbell said. “She keeps me tampered down into the world of reality, and her job as a producer was to present options to me. That was actually her idea because the original story was set in Michigan.”

She sold him on locating it in the Rogue Valley by telling him he could sleep in his own bed every night.

That local-first approach extended beyond the comforts of home into a conscious reclaiming of control.

“It gave me a location that most people would not use,” Campbell said. “Most people would’ve shot this movie outside of Los Angeles or Atlanta or some other hotbed of production, where it would be ‘easier’ with more ‘support.’ I wanted to shoot it specifically here and specifically in June, because that’s the best time to shoot in this state.”

A homecoming

Premiering the film at Medford’s restored Holly Theatre carries special weight for Campbell.

“It’s a way of sharing the celebration with the local people since it was a local production with an Oregon crew and actors,” he said.

It’s especially exciting for Campbell to be showing the film at the Holly, which opened in 1930 and served as a grand movie palace and Vaudeville house, becoming a major cultural landmark before its closure in 1986.

“My favorite theaters as a kid were always the old ancient palaces, creaking at the knees,” he said.

Tying the premiere to the Ashland Independent Film Festival was equally intentional.

“AIFF has made great strides in the last couple years, coming back from the dead, post COVID,” Campbell said.

Beyond the premiere

After its Medford debut, “Ernie & Emma” will continue on a nationwide tour in the fall, including screenings at Alamo Drafthouse locations with live appearances and conversations. Campbell will engage with audiences and talk about the creative process behind the film.

Alamo Drafthouse Cinema was founded in 1997 in Austin, Texas, and now has 35 locations and counting. It built a reputation as a movie lover’s oasis not only by combining quality food and drink service with the moviegoing experience, but also introducing unique programming and star-studded special events.

Campbell looks forward to showing longtime fans another dimension of his work.

“I hope they will see that satisfying stories come in all shapes and sizes,” he said. “There wasn’t anybody writing a ‘phat’ part for me as an actor at this age, so I decided to do it myself.”

In many ways, that decision defines the film’s spirit.

“My definition of success as a filmmaker is if I have the ability to do my job unencumbered, unwatched and unmanaged,” Campbell said. “Like it or not, ‘Ernie and Emma’ is the work of a singular vision supported by many. This movie was not ‘developed.’”

Whether the project proves to be a one-time return or a new creative path remains to be seen. But Campbell sounds certain about one thing: “This process has ruined me. Now I just want to make my own rules.”

Freelance writer Jim Flint is a retired newspaper publisher and editor. Email him at [email protected].