Only experience will determine the wisdom of reweighting the balance between rights and care

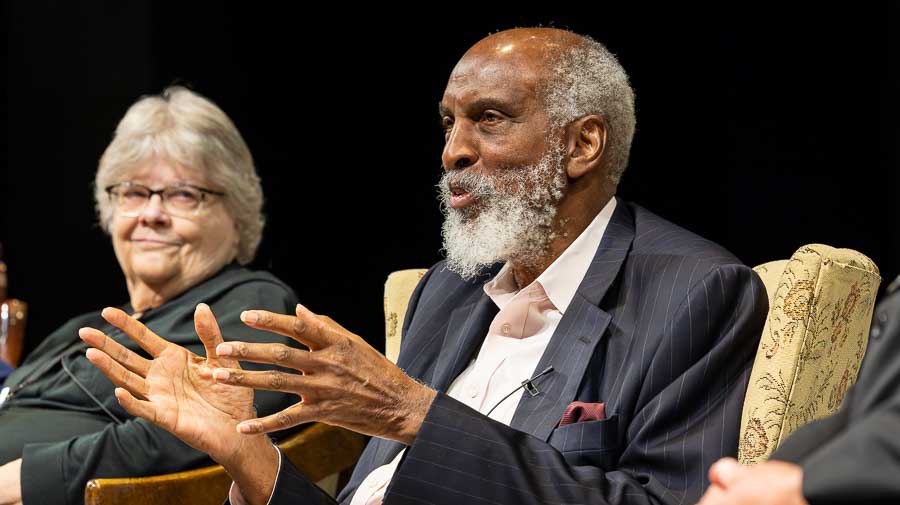

By Herbert Rothschild

In an executive order President Donald Trump issued on July 24 titled “Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets,” he told the attorney general to try to overturn in the federal courts the due process protections that mentally ill people had won in the 1970s. He also ordered the AG to assist states in making it easier to commit the alleged mentally ill against their will.

Along with the title of the order, its next section, “Fighting Vagrancy on America’s Streets,” made clear its intent: to end the homeless problem. This despite no new money for affordable housing and drastic cuts in Medicaid, which pays for a large portion of mental health treatment.

Trump’s effort to hide the evidence of our abysmal social failure dovetails with a properly motivated effort at the state level to get mentally ill people the care they need but are unwilling to seek. From one-quarter to one-third of those living on the street fall into that category.

In 2023, the California Legislature passed a bill establishing CARE Courts, which could involuntarily commit for treatment those who are determined to be mentally ill by using criteria less stringent than the single one established in the landmark 1975 U.S. Supreme Court decision O’Connor v. Donaldson: demonstrably dangerous to self or others.

On that occasion I wrote a column in which I mentioned my deep involvement in the struggle to bring due process protections to allegedly mentally ill people in Louisiana, as well as my distress that, when the big holding pens in the sticks consequently emptied out, states across the U.S. mostly ended their responsibility for mentally ill people instead of putting into place supportive community-based infrastructures.

I discussed the difficulty of balancing respect for individual autonomy with care for those in need. Historically, there was dreadful abuse in society’s treatment of mentally ill people. Endowing them with due process rights in commitment and equal-protection rights in treatment effectively ended that abuse. Neglect, however, was not an acceptable alternative.

I haven’t followed California’s experience with its reform, and I’m not sure Oregon legislators did either before they passed HB 2005 this year. That measure also loosens the criteria for involuntary civil commitment. Specifically, to danger to self or to others it adds, “Is unable to provide for basic personal needs” or “Has a chronic mental disorder.”

I was relieved that the bill does a rather good job making that second additional standard amenable to evidentiary challenge. The less-than-scientific basis of psychiatry and the arrogance of psychiatrists I dealt with back in the day gave me little confidence in the validity of their diagnoses and especially of their prognoses. The first additional criterion, “unable to provide for basic personal needs,” also lends itself to some extent to evidentiary requirements. Still, there is wiggle room for abuse in both.

To the lawmakers’ credit, the bill sets precise and fairly stringent limits on possible abuse. In the bad old days people could be committed against their will for indefinite lengths of time without effective recourse to judicial oversight and relief. HB 2005 specifies the number of days between detention and a court appearance, as well as the number of days in care if the court agrees to a commitment. Further, at the court appearances, the detainee must be represented by counsel “unless counsel is expressly, knowingly and intelligently refused by the person.”

A key player in the commitment process is “the community mental health program director, or designee of the director.” (I doubt if every Oregon county has such an official, but I presume the chief health officer of the county will do.) Following a detention, that official must immediately notify the judge of the court having jurisdiction in that county. If the detainee doesn’t agree to a diversion from commitment as an opportunity for intensive treatment, then a court hearing must be held within five days, at which the detainee has a full complement of rights.

The diversion from commitment may last up to 14 days prior to a mandatory court hearing. Diversion requires the availability of a hospital or nonhospital facility that the community mental health program director and a licensed independent practitioner agree can provide necessary and suitable emergency psychiatric care. The court must be notified promptly of the diversion. Also, the detainee must be accorded the right to refuse diversion and notified of the right to an attorney. With consent, the diversion can be extended for another 14 days at most.

If the court agrees to an involuntary commitment, it can be up to 180 days. Somewhat disturbingly, the commitment can be extended up to 180 more days without a court hearing, although the detainee must be informed of his right to a hearing. Unless I missed something, 360 days is the longest a person can be held. As for treatment, a detainee may not be subjected to “unusual or hazardous treatment procedures, including convulsive therapy, and shall receive usual and customary treatment in accordance with medical standards in the community.”

To the extent I have rightly understood this long and complex bill, I’m going to render judgment on it — a judgment informed both by a strong commitment to civil liberties and a deep desire to help those in need. To it, I invite responses in the form of letters to the editor and op-eds. There are people in this community, such as National Alliance on Mental Illness activists, who have a strong investment in HB 2005. I’m confident that our executive editor will welcome your submissions.

I don’t think the wisdom of HB 2005 can be assessed on its face. It reflects an awareness of past abuses and thoughtfully attempts to guard against their repetition. Yet, there is enough leeway for arbitrary individual discretion and poor oversight that abuses may recur, if not in one county, then in another. Additionally, success will depend upon the availability of adequate treatment facilities and professionals, and that availability is problematic even with the current caseload.

I think this reform is worth a try. As Teresa Pasquini, an activist with NAMI, said when she was interviewed on National Public Radio, “The status quo has forced too many of our loved ones to die with their rights on.” But success isn’t a given. It’s incumbent on its proponents to monitor its implementation closely.

Herbert Rothschild’s columns appear Fridays. Opinions expressed in them represent the author’s views. Email Rothschild at [email protected]. Email letters to the editor and Viewpoint submissions to [email protected].