No other country since WWII has come close to inflicting such carnage

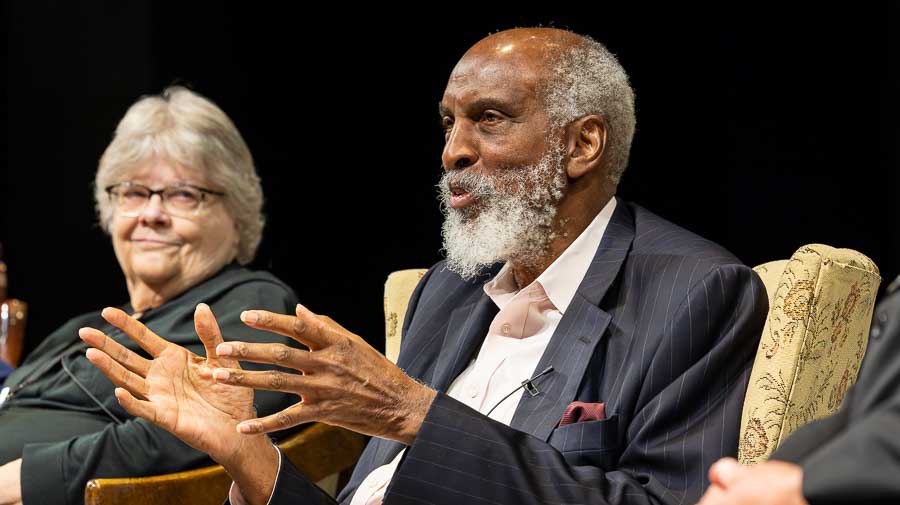

By Herbert Rothschild

Some decades ago — how many, as you’ll see, is beside the point — I was at a peace demonstration holding a sign that read, Stop the bombing. At its conclusion, I was looking for a place to ditch the sign when a friend said, “Keep it. You’ll need it again.”

We live in a country that keeps bombing people who have no capacity to bomb it in retaliation. Here’s a list of them, almost certainly incomplete, beginning in the 1960s: Vietnamese, Cambodians, East Timorese, Lebanese (naval shelling), Iraqis, Somalians, Bosnians, Haitians, Sudanese, Serbians, Afghanis, Syrians, Libyans, Yemenis and now Iranians.

You and I could analyze and debate the merits of each of these actions. After all, smarter people than I did just that and approved them. Yet, if we look at them in the aggregate, what can we learn about the United States of America?

We learn that we are indeed the “exceptional nation” so many patriots boast we are. No other country since World War II has come close to inflicting such carnage on so many different peoples.

And we learn that while we are exceptionally good at killing foreigners, we are exceptionally bad at foreign affairs.

In some cases — Vietnam, Afghanistan, East Timor — after years of killing we utterly failed to prevent what would have happened had we not intervened. In other cases — Lebanon, Somalia, Haiti, Sudan, Yemen — we effected no meaningful change, and I suspect Iran will prove a similar case. In Cambodia, where Nixon’s secret bombing opened the way for the Khmer Rouge to take control, we made things far worse than they would have been.

Perhaps we saved more lives than we took when some states of the former Yugoslavia were at each other’s throats. And whether on balance we helped the Iraqis, Syrians and Libyans more than we hurt them is difficult to determine. What we do know is that several hundred thousand Iraqis died during our invasion and occupation.

But another thing we learn from looking at the forest instead of the trees is that, whatever the results of our bombings, ultimately they make little difference to us. For all the talk about how our military protects our freedom, our freedom has never been affected by the outcome of these engagements.

Indeed, we have been unaffected except for a huge increase of our national debt and the deaths of fewer Americans than those who die at home by firearms every three years. A small number of us care about what happened to the people in the countries we attacked, but the vast majority of us care more about the price of eggs.

And so there’s little chance that our conduct will change. We must stage periodic displays of our might to justify our huge annual expenditures on the military and to give the young men in their pickup trucks some reason to be proud of a country where their chances of thriving diminish year by year.

One way we could do better is if we returned the authority to initiate combat operations to Congress, which is where the U.S. Constitution vests it. Then, the decisions would depend less on considerations of domestic politics, which repeatedly have entered into presidential calculations, and on the mental state of the president.

Lyndon Johnson sent U.S. troops into the Dominican Republic in 1965 to quell an uprising against the military junta that had overthrown the elected government three years before. His motive, he said privately, was that he didn’t want the voting public to think he had allowed another Cuba to establish itself in the Caribbean: “I sure don’t want to wake up . . . and find out Castro’s in charge.” The uprising wasn’t led by communists, nor was the government that briefly ruled, but no matter.

Similarly, domestic political optics largely dictated the way Richard Nixon conducted the war in Vietnam, which he knew could not end in victory. He just didn’t want to be blamed for a defeat. And Bill Clinton bombed the only pharmaceutical plant in Sudan because he felt public pressure to do something after the terrorist attacks on three U.S. embassies in east Africa. Based on one soil sample, the administration claimed that the plant was producing precursors for chemical weapons, a claim that was thoroughly discredited. The only verifiable result was that Sudanese died from lack of antibiotics.

As for President Donald Trump’s decision to bomb Iran, the New York Times published a piece on June 22 about how he reached it. “Mr. Trump had spent the early months of his administration warning Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel against a strike on Iran. But by the morning of Friday, June 13, hours after the first Israeli attacks, Mr. Trump had changed his tune. He marveled to advisers about what he said was a brilliant Israeli military operation.” Netanyahu finally succeeded in dragging us into war with Iran, primarily, it seems, because Trump wanted to share some of the glory.

In 1973, Congress reaffirmed its constitutional authority by passing the War Powers Act. But it hasn’t used it to stop presidents from sending our armed forces into combat without congressional approval. Prior to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, there was a debate and vote in Congress, although the Bush administration had made it clear that it wouldn’t be bound by congressional action. As it was, both houses voted to approve the invasion, with all three subsequent Democratic nominees for the presidency — John Kerry, Hillary Rodham Clinton and Joe Biden — voting for war.

Congress did much better in 2020, when resolutions requiring Trump to get congressional authority to attack Iran passed both the House and Senate with some Republican votes. The Senate, however, failed to muster sufficient votes to override Trump’s veto of the resolutions, which he called “very insulting.”

Following our latest bombing, some members of Congress, including both Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, again have asserted Constitutional authority, and there are resolutions in both chambers — Senate Joint Resolution 59 and House Concurrent Resolution 38 — to remove U.S armed forces from hostilities against Iran because their use wasn’t authorized by Congress. By the time you read this, both resolutions will probably have been voted on, and probably both will fail. Republicans won’t want to directly repudiate their leader on so high-profile an issue.

Into the foreseeable future I’ll hold on to my sign.

Herbert Rothschild’s columns appear Fridays. Opinions expressed in them represent the author’s views. Email Rothschild at [email protected].